A classic paper that informed us, years ago, that orthodontic extractions do not harm facial profiles!

Orthodontic extractions do not harm facial profiles

I am continuing with the theme of orthodontic extractions again in this post. This is in response to comments made by Lysle Johnston and Jay Bowman who reminded me that the effects of extractions had been addressed in the literature. I have, therefore, decided to base this blog post on Lysle Johnson’s classic paper from 1992. I highlighted this work when I discussed the top 10 papers that have influenced my career.

A long-term comparison of non-extraction and premolar extraction edgewise therapy in

A long-term comparison of non-extraction and premolar extraction edgewise therapy in

“borderline” Class II patients.

D Paquette, J Beattie, L Johnston.

AJO-DDO 1992; 102:1-14

Now that I have read this paper again, I think that it is still a classic. The authors start with a really good introduction, in which they discuss the dilemma of whether to extract or not. They point out that if we want to compare extraction and non-extraction treatments this can only be done for borderline cases. They also stated that it would be difficult to randomly allocate patients to extraction/non-extraction treatment in a trial because of consent issues. For example, as part of obtaining consent for a patient to take part in a trial, a clinician needs to inform the patient that one reason for doing the trial is that they do not know the “best” treatment. In other words, we do not know whether it is best to extract teeth or not. As they would clearly choose the least stressful option for themselves, they are more likely to decide that they do not want to take part in the randomisation and they would like non-extraction treatment! This would affect trial recruitment.

They addressed the difficulties of running a trial by adopting an approach that used retrospective data and yet reduced bias.

What did they do?

They carried out the study in several stages;

- They made at least five attempts to contact Class II Division I first premolar extraction and non-extraction cases who had been treated at St Louis from 1969 to 1980 and asked them to take part in the study. One out of nine possible patients accepted this invitation.

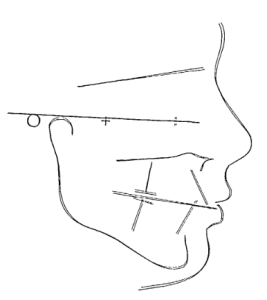

- They then collected data from the patient’s initial cephalograms and study models. They then used this in a statistical technique called discriminant analysis. This grouped samples of patients records together according to their characteristics.

- They then used this data to identify a sample of patients who could have been treated with or without extractions.

- Finally, they contacted 48 extraction and 48 non-extraction patients and obtained a sample of 30 non-extraction and 33 extraction patients. These patients returned for cephalograms, study models and self-assessment of the aesthetics of their profile.

- They carried out an extensive analysis of this data with individual comparisons across multiple cephalometric variables. This was the standard approach at the time.

What did they find?

They found the following;

- 73% of the extraction and 57% of the non-extraction patients had less than 3.5 mm crowding

- The patients did not prefer either the non-extraction or extraction profile

- The lips of the non-extraction patients were 2 mm more procumbent than those who had had extraction treatment.

Their discussion was extensive and logical and I recommend that anyone interested should read it. They emphasised that in their sample there were no differences between the effects of extraction and non-extraction treatments. They also came to the great conclusion that the pressure at that time on the promotion of non-extraction treatment had resulted in the specialty “ being bullied into fixing something that was not broken”. I’m not sure times have changed!

What did I think?

Firstly we need to remember that they published this paper 24 years ago and our knowledge of research methods and statistical analysis have changed. My feeling is that this is a classic paper and all orthodontists should revisit it several times throughout their career.

We should consider how this work has stood the test of time and there are several important points;

- The initial sample of patients that were analysed was 238 out of approximately 2142 patients. As a result, they are a selected group. We need to consider if the people who took part in the study were different from those who did not respond to the invitation. There is no information on this in the paper and this must increases the uncertainty of the conclusions. Importantly, if there is selection bias we do not know its direction.

- There were further dropouts from the final sample and 33 could not attend for records

- Nevertheless, they did identify a group of patients, who were identical apart from the extraction/non-extraction decision.

When I consider all these factors, I can conclude that for these patients, of which there was maximum uncertainty in the treatment decision, the findings were valid.

Overall this paper still provides us with evidence, that for the borderline extraction/non-extraction patient, the decision to extract or not did not have a a clinically significant effect.

My posts this month have being devoted to a theme and I hope readers are finding it useful. I will attempt to summarise the evidence about orthodontic extractions next week and consider a way forwards for clinicians and researchers.

Emeritus Professor of Orthodontics, University of Manchester, UK.

One issue is that they , by selection of their patients out of a broader group, did not compare their cohort to a broader, more normal, cohort. One conclusion could be made is that these faces were already deficient and that the compared treatments did not make them any worse than they already are. However they should have been compared to a “more normal’average” cohort to evaluate the appearance and comparison.

Kevin, I am familiar with the paper by Johnston et al, but that doesn’t explain the damaged profiles

that Tweed published in his book, and that I and many others have produced by relying on hard

tissue measurements for treatment planning. Holdaway was the first to suggest using soft tissue measurements

to evaluate our patients and plan treatments (Holdaway, R.H.: A soft-tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning, Part

1, Am J. Orthod. 84:1, 1983; Holdaway, R. L. A soft-tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning, Part II , Am. J. Orthod. 85; 279,

1984). I think he was right, and that was further corroborated by Alvarez in 2001 (Alvarez, A. The A Line: A new guide for diagnosis and treatment planning. J. Clin. Orthod

2001; 35: 556-608. It amazes me that institutions keep promoting hard tissue measurements as the gold standard for planning treatment.

Larry White

Larry, I think that the “damaged profiles that Tweed published in his book” should be put into context, and for context I mean time, culture, place, race, sex. Aesthetic was different in 50’s and 60’s in Arizona, and we can’t judge profiles aesthetic out of the context.

I’m totally with you when you say that the treatment plan start from the soft tissue, and in the Tweed foundation the golden rule has been “face first” since many years, and bad profiles that we can produce with extractions, in my opinion, are not an ex vs non-ex matter but just mistakes in diagnosis or in managing biomechanics.

Hi Larry, thanks, and yes I agree. If this study was repeated now I would hope that investigators would not confine their measurement to cephalometrics and use 3D measurements.

I couldn’t agree more Larry. Patients today like a more full upper lip as well. I see Cl II transfer cases all of the time with unnecessary extractions that retracts pt A and the upper lip too far.

Now that our (not the royal we/our) papers have been accorded the respect of being worth discussing (nicely done in my opinion), I thought I’d append my interpretation. Firstly, discriminant analysis was used to define “borderline” subjects according to the criteria of the 60s and 70s. It was merely a tactic designed to produce two similar samples that presumably differ only in the treatments they had received. The average difference of about 2 mm is thus an estimate of the effect of “Tweedish” extraction treatments. Our assumption is that this is an additive effect that would apply on average to all similarly executed extraction treatments, today as in 1970. “Similarly executed” is the sticking point. In any event, as a group, our papers argue that for the average adolescent edgewise extraction patient treated without expansion, the following changes can be expected (based on lower lip to Rickett’ E-plane): During treatment, growth will flatten the profile 1 mm and, if 1st bicuspid extraction is employed, there will be an additional 2 mm of reduction; post treatment, growth will add an additional 2.5 mm of flattening to both groups. Lest these outcomes be seen as extreme and aesthetically damaging, it should be noted that, for adult white subjects, about -4 mm is seen as ideal protrusion. These statements are based on averages/means/expected values. A popular rejoinder is the bromide that “wet gloved” orthodontists treat patient one at a time and that, as a result, large-sample averages have no meaning. One at a time, by the thousands over time. Expected outcomes thus tend to keep the clinician’s thinking within the bounds of the likely. Presumably, further research can supply averages based on more precise classifications. (Prediction is like mail delivery, ever more precise classification leading finally to a given address. In other words, we can seek an ever more precise classification for each patient, but in the end when we run out of meaningful categories, our best bet is to anticipate/expect the average outcome for this last grouping.) My first conclusion is that a decision to extract is not an a priori decision to hurt small children for money. Indeed, according to Desirabode and Bridgeman 150-160 years ago (and still accepted), the teeth occupy a position of balance among the envelopes of motion of lips, cheeks, and tongue. Accordingly, a Class II correction is like moving pearls along a string; unless a treatment in some way changes the disposition of the string (i.e., changes the envelopes of function), one would expect little impact on “the airway.” Indeed, absent some sort of ongoing operant conditioning (e.g., a lingual arch with spikes) or some sort of shield worn forever, it is hard to see how muscles can be “trained” to function differently, 24/7. Further, it should be noted that extraction treatments bring the buccal segments forward (about 2mm in the maxilla; 3 mm in the mandible). Absent TADS, only non-extraction treatments routinely “distalize” the buccal segments (upper only, assuming HG and CL II elastics). Secondly, I don’t consider 2 mm a trivial change: for some, it might be the straw that broke the camel’s back; for others—the more protrusive and crowded—it would be a godsend. Freud said that biology is destiny. For this latter category of patient, the choice of orthodontists is their destiny. I would suggest that those who undergo assuasive, popular, easily-sold treatments designed to grow jaws will pay, not only in pounds and pennies, but also (secretly) in terms of regret: the difference between what they got and what they could have got had they had bicuspid extraction ordered by a technically proficient orthodontist. Finally, it should be noted that, according to Little’s irregularity index, our treatments were quite stable long term: half of the non-extraction and two-thirds of the extraction patients had less than 3.5 mm of irregularity. Alongside this finding it should be noted that the treatments were executed essentially without expansion, both at the canines and the molars. I will leave it to the reader to infer causation.

So for whom is 2 mm adaptable and when will it break the camels back? Air flow is calculated to the 4th power so 2 mm could reduce flow by 16 times. That might not be trivial as you said.

We just don’t know how the human will adapt to a retrusion of 2 mm and a possible reduction of the airway. Why not intervene earlier with expansion in those kids with narrowed airways combined w T and A and Myo if necessary

Kevin, this study, unfortunately, was made in a 2D setting using 2D Cephalometrics which is all we had at the time the article was written. However, a person’s profile is only part of the equation. With cone beam x-rays, we now are living in 3D reality. We now know that current 3D thinking takes into account things like upper airway, maxillary arch width, tongue space and posture, and we now have to consider the effects of extractions versus maxillary expansion on future conditions such as TMJ Dysfunction, Obstructive Sleep Apnea and even Cervical spine stress due to a forward head posture accommodation. I will choose slow maxillary expansion to achieve an ideal arch form over extractions which leave the constricted maxillary arch. Because of current 3D thinking, this study should no longer should guide our treatment other than as an example of some orthodontic past thinking.

Thanks and I agree that if this study were done again today, I would expect to see 3D measurement. Nevertheless, I still think that it provides useful information to contemporary clinicians. It would be great to see studies done on this using 3D technology.

It would be even better if we were to convince Archangel Gabriel to descend and tell us the answer. Failing that, it is almost equally unlikely that a long-term orthodontic study of anything by way of CBCTs would be allowed purely for the sake of research. Again, it’s do anything you want until something that probably can’t happen occurs. In the meantime, it’s the uncritical selling the unlikely to the unknowing.

Thanks again for another wonderful post. Sometimes we need a little refresher.

An excellent post, and a very informative discussion.

As an aside, bicuspid extractions don’t always have to mean first premolar extractions. Several cases with milder protrusion/crowding can be treated very nicely with the extraction of second bicuspids, as evidenced by the work of Dr. Boley and others.

The current trend towards erroneously conflating premolar extractions with OSA/dished-in profiles/narrowed arches etc. is not substantiated by the evidence. Patients (and parents) can appreciate the improvement in lip support, facial balance, and esthetics especially when before and after images are presented in cases that were attempted non-extraction, and eventually treated with extractions. This case report by Dr. Bilodeau represents a great example of this.

Bilodeau JE. Retreatment of a transfer patient with bialveolar protrusion with mini bone-plate anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014

Oct;146(4):506-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.11.023. PubMed PMID: 25263153.

It’s now known that cephalometric analysis does not exist in true 2D or 3D space. Studies relying on conventional cephalometric analysis need to be viewed ‘with a pinch of salt’, meaning that the findings cannot be entirely relied upon. Please see; Moyers RE, Bookstein FL. The inappropriateness of conventional cephalometrics.

Am J Orthod. 1979 Jun;75(6):599-617.

Honoring this paper as a standard to be upheld is like upholding the victrola as the standard for listening to music (how’s that for an opening?). With all due respect to Dr. Johnston and the support he has given to the EBD segment of our profession, this paper – along with many more recent studies (to be mentioned momentarily) – only helps to justify the status quo of orthodontics as a compensation for a deformity rather than to help raise it to the level of a correction which is so sorely needed in our time.

Now that we are considering the teeth (and their occlusion) as part of the person they are attached to (rather than just “plaster on the table”) we need to also take responsibility for the interaction between the oral and general physiology. “Do no harm” is necessary but no longer sufficient. “Do good” has to be the ideal we rise up to.

In a paper of a similar theme – and one I am sure you will want to feature on this blog, Kevin – Ann Larsen (1) begs to show that premolar extraction does not “cause” obstructive sleep apnea by showing her cases with “missing” premolars” having the same incidence of OSA as do non-extraction cases (approximately 10%). Well, big whoop. Why is it OK to let people get sick? If we recognize that people are suffering, don’t we have an obligation to help them get better? Sleep apnea, and all of its flow-limitation precursors, are directly linked to facial morphology as a primary risk factor(2-6, among others), an area of direct responsibility of the airway-aware orthodontist.

I want to challenge the assumption that even though we know that “muscles win” (Thank you for that acknowledgement, Dr. Johnston), that we don’t have the ability to change postural and muscle patterns in children (or adults for that matter). The habits that create the distortions in the maxilla are themselves a change in muscle patterns in response to some chronic stressor (ie: respiratory, inflammatory, nutritional, birth traumatic, postural, etc. etc.). If habits can be changed from health to unhealthy, why can they not be changed back again? Of course they can. We do it everyday in practice.

That brings up my second challenge, as you may expect, of the assumption that the skeletal deformities resultant of these habits are the only possible outcome for these patients. If the maxilla collapses (in all three dimensions of space, mind you) from lack of muscular support (as in open mouth posture), why must it be accepted that this is “what this child has” and not “what this child is becoming”? Again, in practice we are reversing these conditions every day (in three dimensions of space, mind you). So why do we have to accept compensatory treatments, such as premolar extractions as acceptable? Compensatory treatments may not cause the problem and may not even exacerbate the problem, but they serve to perpetuate the problem forever by their ignorance of the problem.

I am coming to resent the (self-serving, defensive) attitude that orthodontics is not culpable as long as it’s doing no harm. It’s high time we become much better than that.

Barry Raphael

1. Larsen, Ann, J, Clin Sleep Med, 2015.11:12, 1443-1448

2. Aihara K, et. al ,Sleep Breath. 2012 Jun;16(2):473-81. Epub 2011 May 15.

3. Dempsey, et.al., CHEST September 2002 vol. 122no. 3 840-851

4. Lowe, et. al. AJODO, 90: 484-491, 1988.

5. Ikävalko, et.al.,Eur J Pediatr (2012) 171:1747–1752

6. Major,et.al. J Dent Sleep Med, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2014

I think that the fundamental flaw in this study can be summarized in the following statement taken from the paper.

Nevertheless, they did identify a group of patients, who were identical apart from the extraction/non-extraction decision.

These patients might have appeared to be ‘identical’ from an Angle Classification point of view, as well as 2D Cephalometrics (which provide dubious data), but what of all the other points of functionality which have a DIRECT bearing on the integrity of the jaw, mouth and teeth? It is unlikely that even two of these patients had the same underlying issues in terms of posture (tongue as well as body), sleep and breathing integrity and morphological similarities.

The knowledge and the tools that we have today, together with the scores of people we encounter, post extraction, who have major sleep and craniofacial pain issues, has to cause us to take a much deeper look into what is, by today’s standards, a superficial conclusion.

Please take this from the viewpoint of a clinician that has had no interest in the field of orthodontics during his 40 year dental career, but who has spent the last 22 years dealing with adult airway management and sees the result of serial extraction in his adult patients every day. Why is it that patients that have had serial extractions account for about 50% of the thousands of adult patients I have treated, irrespective of BMI?

When looking at a study, I like to see what kind of information has been taken into account to validate the study. Were the participants screened pretreatment for mouth breathing, nasal patency, posterior crossbite, tongue tie, degree of tongue tie, presence of any degree of tongue thrust, palatal height, presence of tonsils and adenoids, resting tongue level, proper swallowing pattern, eye shadowing, standing side plumb line, history of ADD/ADHD, intact lip seal, snoring or habit history. I think I already know that answer since the majority of orthodontists and general dentists today would need to ask why some of the above have to be addressed, much less when this study was published.

If the study foundation is faulty, how can you research an entity and then say you have normal results? First the clinician must have to have some knowledge of Sleep Disordered Breathing (SBD) in the child and adult. Then ask yourself why SBD is a disease of the developed world, not third world where breast feeding is prevalent. Then you have to understand how breast feeding and its impact on the genioglossus and how its impact on the development of the oral-facial complex occurs. I know I am getting off the subject, but the subject tends to do this on its own. So if you wanted to see if serial extractions were iatrogenically causing airway issues, would you not want to start with a “normal” patient population, not one that is already compromised from many of the issues I have listed above? Hasn’t anyone every asked why serial extractions are probably an insignificant procedure in populations that are predominantly third world breast fed populations?

So what I am seeing is a study that has a faulty patient population to begin with where normalcy is unattainable unless the underlying causative issues are addressed. In this study they don’t appear to have been so for me it has no validity at all. The term “you can’t see the forest from the trees” come to mind here. Essentially they took a mouth of crowed teeth that was already compromised for area for the tongue and airway, made it smaller with serial extractions and straightened the teeth with a cosmetic result. Once a class I occlusion and nice smile have been obtained all is good. This total discussion reminds me a chapter from the book “Century of the Surgeon”. The surgeon would remove the thyroid and his patients became well. He was a hero until one day years later a patient returned to his clinic as a cretin.

As I stated from the beginning, I have limited knowledge of the orthodontic field. I just deal with the results of what this study calls normal every day. Before one corrects a problem, shouldn’t one have a better knowledge of what caused it and the long term impact on the associated structures in relationship to the overall patient’s medical history. It seems like some want today’s knowledge to justify yesterday’s lack of.

Thanks Roger and Martin, you make interesting comments and I would like to follow them up. Can you refer to some publications that would provide me with some evidence that underpins your comments?

Dr. Johnston, Many of us “unknowing” have known for some time that there is a bigger picture of orthodontics that has yet to be defined by the literature. To keep things in the UK, where this topic is soon to heat up, here is an example of what is known by an Irish ortho-dentist, Dr. Tony O’Conner (and yes, perhaps us specialists should be humble enough to listen to others without a specialty education…): http://www.irelandsdentalmag.ie/index.php/articles/pm_article/orofacial_myofunction/

The accuracy of conventional cephalometrics has been called into question over a number of years. Yet despite this, many “scientific” research papers draw their conclusions from these analyses.

During 30 years of functional orthodontic practice my aim was as much about enhancing the facial aesthetics as it was about correcting the malocclusion. In the latter years, improving the airway also became a very important part of the equation.

In my opinion, orthodontics seems to go against the grain in several ways. Most developmental problems are dealt with when they are diagnosed, whether in dentistry or medicine. However, in orthodontics, treatment may be delayed for many years without even consideration for interceptive techniques.

In nearly all walks of life, changes have taken place during the last 30 years and that is true for medicine and dentistry. For some reason orthodontic treatment has, with the exception of some bracket and wire tweaking, remained fundamentally the same. Despite the fact that life long retention is now the recommended norm there has been quite fierce resistance within the profession to explore any alternative approach to treatment. Is this really a true reflection on a scientifically based speciality?

Barry Raphael is exactly right with his comments about Dr Johnston’s 24 year-old paper that attempts to justify premolar extractions and is still regarded as valid today by some.

However, I would go a little further and describe conventional extraction orthodontics not just as ‘compensation for a deformity’, but as actually fixing that deformity permanently in place (without actually addressing it) with an ‘improved’ occlusion due to failing to recognize the problem. The maloccluded teeth are simply signposts telling us what is wrong and which way to go to correct it; they are not the problem per se.

Leaving out the debate about the seriousness or veracity of the unintended consequences of extraction orthodontics (TMD, airway issues, etc.) there are two major issues that disturb me:

Firstly, the majority of orthodontic extractions are carried out at the start of the pubertal growth spurt – the time in a child’s life when their skull and face bones are developing downwards and forwards with maximum speed and force. Yet this is considered the ‘best’ time to introduce retraction mechanics!

Secondly, extracting maxillary premolars or molars and closing the spaces will reduce an average 130mm maxillary arch length by a certain percentage. Can it be true that all crowding cases can be fitted into precisely the amount of space such extractions provide without altering the dimensions of the arch? I think not.

I am constantly amazed that we still need an evidence base to convince ourselves as a profession that we are doing the right thing by amputating children’s healthy teeth for orthodontic reasons.

Kevin, I have nearly finished that list of references you asked for in an earlier blog.

do take a look at my situation (before and after cephs at bottom of page)

https://www.righttogrow.org/rachel_s_story

Premolars removed age 9 (before full eruption) after serial extractions and retractive mechanics until age 13 then retention.

All I can tell you is that my profile, TMJs and health have caused me 30 years of suffering. I have twice tried and failed to improve the situation orthodontically.

It is easy to dismiss a case as a bad job or say that the patient is crazy, but where can the justification be for doing this to the life of another human without their consent and then refusing to see the obvious? one wasted life: and I know I am not alone

The problem with these claims of functional orthodontics, is that there is simply no evidence that it works (or even evidence to the contrary). If only the proponents who make such claims would understand, and apply the scientific method. An alternative method is fine, but who is to say that it actually works? The proof is (or should be) in the pudding. It is not difficult to design an RCT to evaluate these things – why have we not seen such research from the vocal advocates of these questionable therapies?

There is probably no evidence at all proving beyond doubt that it is safe for us to get into our cars and drive home at the end of the day’s work, but we all do just that and the vast majority of us manage it in complete safety. We continue to do so day after day without really giving a thought to the fact that we know there is no evidence that it is safe to do so. We even sometimes carry our friends and family in the back in the knowledge that no one has proved that this is completely safe.

I have become rather tired of the attitude that “you must not do anything in orthodontics unless the science says you can”. How on earth did any of this stuff get started? By orthodontists trying something out to see if it works – anecdotal evidence from serious real-world orthodontics. The science came later, if at all.

If there isn’t any science to support functional orthodontics, there jolly well should be! I was practising it for 25 years before I retired and I can assure you – IT WORKS! Thousands of orthodontists around the world would tell you the same.

But there is one very good reason why there may be a dearth of ‘scientific’ evidence; the vast majority of this kind of advanced functional orthodontic treatment is done outside the establishment and NHS hospitals, in GDP High Street orthodontic practice. They do not have the time, resources or the money to set up, run, manage, supervise, collate and report, then publish such a piece of academic work. Do we get requests from scientific and academic quarters to provide material for such an RCT? No. This is a pudding that no one is likely to bake.

What makes a person/group’s anecdotes more believable than another person/group that profess the opposite perspective? Appeals to authority/experience/magical insights etc. are not consistent with the scientific method. You can certainly do things, but to make claims of superiority/therapeutic efficacy etc. needs control groups, and the other rigors of research. On the flip side, why do something that doesn’t have proven benefits? While that may have worked in the past, there really is no excuse for that sort of primeval thinking given the technology at our behest.

It is incumbent on those who make these assertions to provide the data. Consensus does not = Truth. It can just as easily be the wrong opinion of several. After all, didn’t a majority of people believe at one time that the earth was flat?

This paper is often cited in the argument that facial aesthetics are not compromised with extraction based treatment. Yet their studies found a 2 mm more procumbent lip profile in the non extracted patients? How does having this huge loss in lip volume and support after extractions not compromise aesthetics?

Is lip retraction always unesthetic? The answer – it depends! If the lips are protrusive, facial balance improves with retraction.

I would very much disagree, there are very few cases, in my opinion, where facial aesthetics improves considerably with a loss of lip support. Fuller lips are aesthetically pleasing and this should always be a primary concern when devising a treatment strategy.

Dear Kevin,

Living as I do in quiet retirement in a town of 35 in Northern Michigan, I am surprised to learn that there is a parallel universe (a flat world, actually) in which there are no grossly protrusive profiles for which a bit of reduction would be a godsend. Given that no patient dies from bizarre therapeutic expectations, anything and everything apparently work well enough (or can be said to work well enough) to pay the bills. Is this a great specialty or what?

As an aside, the only purpose of the offending, elderly paper was to estimate the long-term (14+ years) relative effect of first-bicuspid-extraction on the profile (2mm), on the TMJ (nothing), and on the patients’ aesthetic preferences. The study was conducted at a time when the intellectual vandals were at the gates claiming that bicuspid extraction had an unavoidable, gross negative impact on profile appearance, accompanied by a distal mandibular displacement that doomed the unfortunate patient to a lifetime of joint discomfort. Now it’s airways, sleep, and myofunctional therapy reincarnated, world without end.

When Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Georgetown, his band played The World Turned Upside Down. It’s time that we turn things upside down: until the devotees of the various new age treatments provide something in the way of

proof, we orthodontists should be wary and very skeptical. In the meantime (it will be a very long wait), our few remaining academics would be able to do better things than play “whack-a-mole” with the strange–but salable–ideas that crowd for attention in the orthodontic marketplace.

Oops! The surrender was at Yorktown, rather than Georgetown….

At this point perhaps attention should be brought to the fact that Professor Kevin O’Brien has,on several occasions, acknowledged that despite there being a multitude of papers there is, in fact, no robust scientific evidence in orthodontics. Hence the need for this endless discussion. Therefore, when a prominent figure, such as Dr Martin Denbar, takes the trouble to post a comment on this website detailing his clinical observations his views should not be dismissed without due consideration.

Hi Helen, you have actually misquoted me. I don’t think that I have ever said that there is no robust scientific evidence in orthodontics. There are plenty of really good trials and systematic reviews that evaluate common clinical problems and solutions.

When the world WAS flat, someone came along to say it wasn’t (and were well persecuted for the notion). Pertinent to this discussion, I’m not sure which side is “flat”. But just for the fun of friendly argument, let me propose a concept that is just as revolutionary: What if the concept of “Bimaxillary protrusion” was a misnomer. What if, given the changes well documented in the anthropologic literature to the human face (see Lieberman, Corruccini, Gluckman, Price, Larsen, Gilbert and others for the “evidence”), that these cases are actually “Bimaxillary skeletal retrusion” with the teeth in the CORRECT place?

When the world WAS flat, someone came along to say it wasn’t (and were well persecuted for the notion). Pertinent to this discussion, I’m not sure which side is “flat”. But just for the fun of friendly argument, let me propose a concept that is just as revolutionary: What if the concept of “Bimaxillary protrusion” was a misnomer. What if, given the changes well documented in the anthropologic literature to the human face (see Lieberman, Corruccini, Gluckman, Price, Larsen, Gilbert and others for the “evidence”), that these cases are actually “Bimaxillary skeletal retrusion” with the teeth in the CORRECT place? Would retraction of the teeth to match the already-misshapen face be appropriate then?

Only in a calling in which nobody dies from treatments generated by crazy ideas could such a rationalization be generated. O.K., I’ll play along. What does one do about teeth that are in a correct position for neanderthals? Suggest time travel? Grow the face forward and then give mom a bunch of bananas? So much for orthodontics as a learned calling.

I suppose, to the ardent disciples of the pyramid of denial, and the triangle of disbelief, bicuspid extractions always lead to a litany of (imagined) horrors.

While this might be a shocking revelation to the afore-mentioned, extractions and good lip support are not mutually exclusive. When one assumes extreme positions on any topic, it is challenging to accept and understand the subtleties and nuances integral to the question.

Drs. Johnston, Boley, Vaden, Gianelly etc. through their excellent research efforts have already proven that the earth is indeed round (or that extractions do not lead these imagined horrors). Now, it is time for the flat earth society (aka the purveyors of these “revolutionary” ideas) to support their specious hypotheses, with research and evidence. We all have clinical observations and individual experiences; however, the plural of Anecdote is not Data. Additionally, no figure is so prominent that their claims do not require substantiation by science. Appeals to authority/experience/biological plausibility only serve to detract from the argument. The proof is (or should be) in the pudding.

For those that insist on hiding behind “the data”, I will say that – in defense of anecdotal evidence – if something was done well, then n=1 can be a beautiful and edifying thing.

Take for example, Dr. Marianna Evan’s beautiful and courageous results, in defiance of the data.

After you look at this case, ask yourself if you would want your child to have the first-planned treatment, or the chosen treatment.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=882574831841915&set=pcb.1703085779977871&type=3&theater

Words like Beautiful, Courageous, Defiance are epaulettes befitting the fictional reality that they attempt to validate. It is imperative for practitioners stuck in the dark ages to realize that science relies not on emotion, but on data. It might have been Bill Proffit that noted ““Enthusiastic reports tend to lack controls; well-controlled reports tend to lack enthusiasm”. Are we (as orthodontists) a scientific specialty, or purveyors of the theatric arts? Do we doff our proverbial hats to the edifice of evidence only when it concurs with our “emotions”?

“Beautiful”, in that she created not only beautiful occlusion (scientifically defined as Angle Class I with adequate guidance, etc), but also a beautiful face. If you need evidence to see the facial improvement, look at Mark Ackerman’s work.

“Courageous”, applies. Can you imagine what it took to say to the parents that though her premolars were already extracted there is a better way? And the time and care it took to help the parents and patient understand what she saw? It would have been very easy to just say, “Well, what your orthodontist is proposing IS the standard of care”. But she didn’t, in Defiance of the data….

This is a fabulous discussion that needs to take place. The only problem is that most research occurs at the dental schools. When I have contacted all three dental schools here in Texas and tried to discuss mouth breathing, the airway and the new research on its impact with neurocognative defects with the Pedo or Ortho department chairs or profs I am either ignored, phone calls not returned or given my obligatory few minutes to talk and then ignored with a gracious good bye.

Back around 1999 I was involved with a case of Combination Therapy with a very severe OSA patient, AHI of 85. After successfully controlling the case and eventually publishing the case report I contacted the Dental School in San Antonio to discuss the case and possibly involve them in this new field of Dental Sleep Medicine. I was informed that I should not be doing what I was doing and thanks for the info. but no thanks, don’t call us, we will call you if we are interested.

I agree that research is necessary but I feel like history is repeating itself. I am not an orthodontist but when I see the results of so many adult patients having gone through serial extraction 20+ years after the fact, I have to ask myself about the cause and effect relationship of the procedure. Turning a blind eye to it and proclaiming there is no research when it is near impossible to have the departments doing the bulk of the research ignoring the issue is a bit disingenuous. It has taken 20+ years to get the field of Oral Appliance Therapy to begin to be accepted; still some hold outs in the medical world, here in Central Texas. I fear working within our profession may take longer to find the answer and accept the results. Time will tell but I wish more in dental academia would be open minded and not so protective of their sandbox.

That exact question has been conclusively answered by Larsen et al., and the study design discussed in another of Dr. O’Brien’s blog posts. What did they find? The prevalence of OSA was identical amongst subjects with or without premolar extractions. Therefore – No cause and effect relationship. It is simply scientifically invalid to reach a priori conclusions, and then attempt to make the facts fit (or refuse to accept facts that don’t fit the foregone conclusions). That is a very typical flaw, and indicative of a confirmation bias. Scientific research (depending on the design) can eliminate or mitigate several of these biases, and help us reach accurate and meaningful conclusions. Thus, keeping these findings in mind, one has to ask if we are ever willing to accept scientific research over our personal anecdotes? Or do we just keep asking the same question over and over again, until we hear the answers that suit us? Denial is not just a river in Egypt.

I have not read the study recently and I can appreciate what you are saying, but no one study should be considered the holy grail of anything, particularly since there are so many variables that probably had not been considered. I may be wrong, but did the study screen for nasal patency, swallowing patterns, mouth breathing, Mallampati score, head position, age (significant airway issues do not develop until later in life), sleep disordered breathing (most young patients are unaware of UARS thinking their symptoms are normal), adult nocturia, bruxism, reflux, depression, high blood pressure etc. at year 14.5. Issues of sleep disordered breathing arise after the age of 30 caused by issues created when treatment was done in ones childhood and teen years. and that is what I am seeing.

Please don’t tell me that the 45 year old patient sitting in my chair with their first bicuspids missing from serial extraction, their tongues hanging over their teeth and highly scalloped (don’t know where to put it at rest), an AHI of 30+, BMI < 30, nadir high 70%, high palatal vault, low tongue level, mouth breather, forward head position with their lateral plumb line, significant bruxo-faceting, etc. has not been impacted by the lack of simple space in the oral cavity due to the reduction of space from the loss of their bicuspids when they went through ortho. as kids. I am not insinuating or emphatically stating the ortho. is 100% the issue, but it is an issue. The duck is quacking.

This goes to the problem of tunnel vision and being a tooth mover and fixer philosophy vs. integrating the oral cavity into the complete person as a whole, airway centric dentistry. This is the future and I would hope our institutions would quite looking to the past to justify the future when there are reasonable questions being asked. Take a look at Brian Palmer's work, look at populations that are breast fed vs. bottle fed and ask yourself, why is serial extraction a therapy of effectively only of the developed countries of the world. To many questions with real results happening to real people seen every day with the same history of bicuspid extractions for me to think this one study is golden.

Denial comes in all forms, including the way you read into the evidence. For instance, you may be happy that the Larsen paper exonerates orthodontists for responsibility for OSA, or you may be sad for the opportunities missed to help these people away from the primary risk factors that caused their disease, ie: facial morphology. (Please excuse my use of terms connoting emotion. I do think they apply).

While indulging in fallacy (and fantasy) can be entertaining, these assertions lack evidence. Orthodontists cannot be exonerated from causing OSA, TMD etc. since they were never convicted to begin with.

How is it that some of us continue to promote, and sell this concept of “helping people …their disease” with no evidence to back up these nebulous claims?

This is unfortunately not a zero sum game – one has to consider the burden of treatment, both from a financial and physiological perspective.

People can certainly have their opinions, (unsubstantiated as they are) but not their own facts. Happiness/Sadness etc. are really not germane to the discussion at hand, and are not a part of the diagnosis or treatment planning process.

This wealth of sentiment would be better expended in trying to comprehend the nature and magnitude of cognitive biases that seem to punctuate these non-scientific theories.

I can speak from my own experience in saying I immensely regret putting my trust into an orthodontist who decided I needed four teeth extracted, two upper on each side and two lower on each side. Subsequently, I developed very loose teeth and actually had to have another tooth removed which was just hanging by a ‘thread’. The periodontist told me that loose teeth were common following extractions and banding. Consequently I have had a dramatic lower facial collapse with pronounced marionette lines, sunken cheeks and a loss of lip volume. My smile now is just awful and I am very self conscious and embarrassed. I would never recommend extractions to anyone contemplating orthodontic banding. My smile prior to banding was much nicer even with the tiniest bit of crowding. I have lost all faith in dentists and dental specialists and have wasted thousands of dollars for a terrible outcome.

So, how, really, do we determine what works, as a midline (no pun) for every one when we are treating genetically different individuals? Its a rhetorical question. I can’t answer it either. However, to me the classic article that answers the question (for me) is an article in the British Dental Journal entitled “An Orthodontic Challenge.” It is introduced as: “This case report describes the orthodontic “decrowding” of a pair of identical twins,(twelve year olds) one by conventional extraction therapy, the other by use of a functional regulator. Brit.dent.J.,1976, 140,96.

Before treatment, it is difficult to tell a difference between the two girls. In the “after treatment” photos, the two girls do not even resemble sisters. The twin with extractions, sadly, is acutely aware of the difference, has developed an inferiority complex, and has made her the “ugly sister.” The post treatment photos are dramatic. The facial bones stopped developing after the extractions.