A Point-Counterpoint discussion on Hemisection for mandibular primary second molars

This is a discussion about the interesting RCT on hemisection for space closure for missing mandibular primary molars that I posted about. The results of this trial were discussed in depth on social media, and I thought we should cover some of this discussion on my blog. This post includes contributions from Martyn Cobourne, Jörge Glockengießer , and Julia Naoumova, who is the author of the paper. I also decided to comment!

Martyn Cobourne’s thoughts?

Most people would agree that agenesis of mandibular second premolars is best managed by extracting the retained primary second molars and closing the space whenever possible; this can be acheived through spontaneous space closure after interceptive extraction or controlled closure with a fixed appliance. A proactive interceptive approach involves hemisection of the mandibular primary second molar during the mixed dentition, with initial extraction of the distal part, followed by the mesial component, to promote space closure through mesial movement of the first permanent molar whilst maintaining control of the mandibular centreline. Hemisection may offer more control of spontaneous space closure and better occlusal outcomes, although it does involve two separate procedures under local anaesthetic. This practice is uncommon in the UK (indeed – I have never prescribed it); however, it remains popular in parts of Europe. My friend and colleague Jörg Glockengießer has demonstrated some impressive cases using hemisection. We discuss this method within the context of a recently published trial—viewing it from the perspective of someone who is fairly ambivalent towards hemisection (never having prescribed it) and someone who employs it more regularly under appropriate circumstances.

The randomised controlled trial

The single centre split-mouth randomised clinical trial was published in the European Journal of Orthodontics and led by Julia Naumova https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40501277/. This trial has received quite a lot of positive attention in various online fora over the last week or two (Evidence Based Orthodontics; KIEFERORTHOPÄDIE; Orthodontics Mastery Group), and this blog.

In summary, this RCT involved 40 participants with bilateral agenesis of mandibular second premolars and an overall mean age of 10.31 years at extraction. Hemisection and distal extraction (with no endodontic treatment of the retained mesial component – rarely needed, according to Jörg) or conventional extraction of the whole tooth were randomised on a split-mouth basis. For more information, please refer to this blog post. The overall conclusion from the study was

“Hemisection is not recommended as an interceptive extraction option for patients with congenitally missing mandibular second premolars, as only minimal, clinically irrelevant differences were observed compared with conventional extraction. Moreover, hemisection is associated with increased costs and a higher risk of complications.”

The ambivalent (Cobourne) view is that the multiple surgical interventions under local anaesthetic, increased post-operative problems, increased overall cost and lack of clear clinical advantages identified in this good quality RCT confirm that this intervention is generally, not worthwhile. I would argue that these cases can be managed more easily with extraction of retained primary second molars in the early permanent dentition as part of a comprehensive treatment plan involving controlled movement with fixed appliances. Less intervention, less visits and less unpredictability, but Jörg is a very thoughtful orthodontist, and he has made some interesting comments that I had not really considered.

Jörge Glockengießer’s comments

The more committed (Glockengießer) view would argue that a split-mouth trial investigating bilateral agenesis of mandibular second premolars would, at first glance, seem to be a reasonable methodology for investigating space closure in response to hemisection.

However, whilst this might be true for bilaterally absent mandibular second premolars, hemisection is actually far more useful for those (much more common) cases that demonstrate unilateral agenesis of mandibular second premolars.

In unilateral cases, symmetry of the mandibular arch often has to be preserved and care taken that the midline does not shift to the side of the agenesis. Indeed, the function of the mesial root of the hemisected primary molar is crucial for the preservation of arch symmetry. It serves as a book-end and thus keeps the incisors in place, preventing a midline shift. Patients with bilaterally missing mandibular second premolars often have very different anchorage needs in association with the anterior dentition compared to cases with unilateral agenesis.

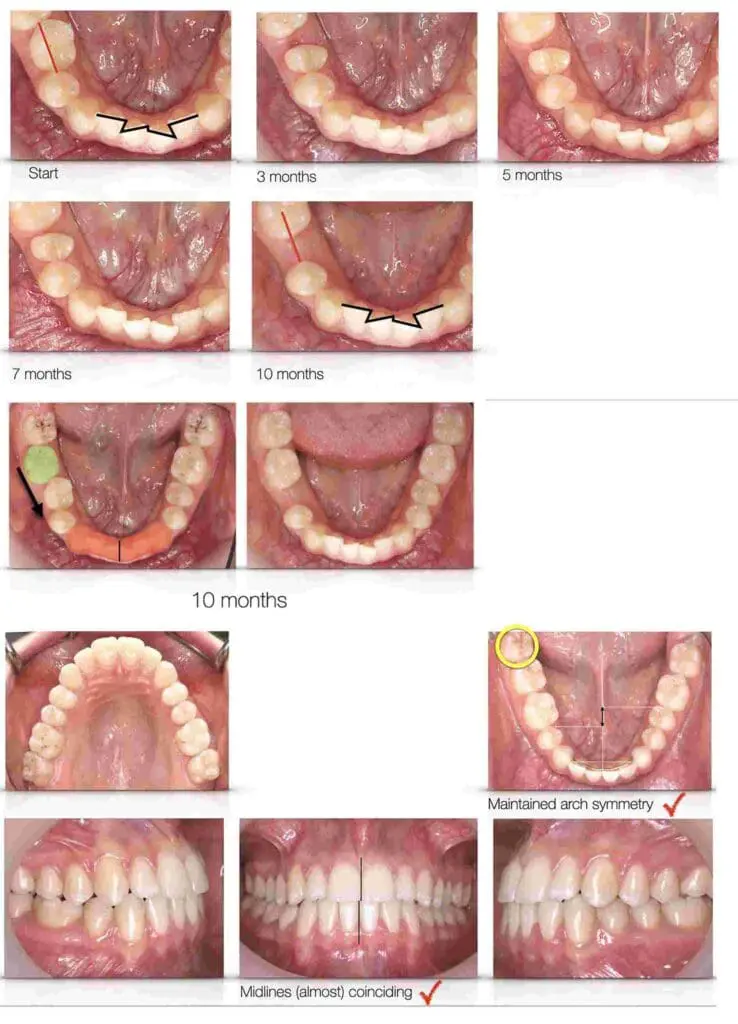

Furthermore, treatment for space closure is a lot more challenging in unilateral cases. This is illustrated with an accompanying case.

The patient was a 15 year-old girl with LR5 agenesis. With hemisection of the LRE, the LR6 was able to drift mesially. The amount of space closure needed is indicated by the red line. After 10 months, half of the lower LRE space had closed – by doing nothing except hemisection! Most likely, the speed of this mesial drift and the extent of tipping would have been exactly the same without hemisection; a simple extraction would have produced the same effects on the LR6. BUT, imagine the consequences if this treatment had been carried out. The lower incisors would have shifted to the right. An unwanted movement that can be very hard to correct. With hemisection, this effect was prevented. You can see, that the incisor irregularity did not change at all during this 10 month period. This shows quite impressively the “book-end” function of the hemisected mesial segment. In the end, the space reduced just by itself, by half.

Other comments?

We also felt that John McDonald made a useful point in the previous conversation on Kevin’s blog. We quote “the decision to extract the mesial fragment when there was 2 mm of space between the molar and the mesial fragment was surprising. This is not something I had heard of and I wonder why this approach was chosen? In my cases, I allow the molar to drift all the way to the mesial fragment and even slice more from the mesial fragment to allow continued mesial drift. I don’t have the mesial fragment removed until I am ready to complete space closure in full braces. In fact, in this study, time between extraction of the mesial and distal fragment was 10 +/-4 months, whilst the time between T1 and T2 was 4 years or more. That means that for 3 out of the 4 years of the measured period, both sides were essentially the same, that is extraction of the tooth. Not surprising, that the results showed no difference over that time-period. I am not sure this study closes the door on the viability of the Hemi section procedure”.

Possible summary of clinical experience and high-level research?

- Hemisection is not helpful in bilateral agenesis cases for patients aged around 11 years;

- Hemisection can be a very simple and effective tool in unilateral second premolar agenesis cases, where you want to treat the patient with unilateral space closure.

- Don’t forget the “book-end” function of the mesial part of the hemisected molar. It maintains the symmetry of the arch and ensures vertical eruption of the first premolar in unilateral cases.

- Hemisection in unilateral cases can be a super-simple and effective tool.

Julia Naoumova Response and Clarification on Study Design and Clinical Relevance

Thank you for the thoughtful feedback and interest in our study. We appreciate the opportunity to clarify some important aspects of the design and rationale behind our choices.

Although bilateral cases are less common in clinical practice, they were deliberately chosen to enable a split-mouth design. This approach reduces the influence of inter-individual variability and strengthens the internal validity of our comparisons. Regarding patient age, the mean was 10 years—not 11. As mentioned in the introduction, aplasia is typically diagnosed around age 9. Therefore, extraction between 10 and 11 years aligns well with current clinical timing and does not represent a delayed intervention. Root development of the second molars was also evaluated, and most patients showed similar development stages. Importantly, root development did not prove to be a predictive factor for space closure in our results.

Regarding the space criteria for extraction of the mesial root, we used a threshold of 2 mm or less to guide the timing of extractions. Since patients were recalled at regular intervals, this threshold helped standardize the timing of extraction. While waiting for full spontaneous closure could be considered, accurately identifying that point across patients is challenging. As with all study designs, practical decisions must be made to ensure consistency while maintaining clinical relevance.

We are aware that extracting a second primary molar and following up with fixed appliance treatment is one option. However, the purpose of this study was to investigate the outcomes of extraction without additional intervention. Understanding what happens in these cases without further treatment is highly relevant for evaluating the effectiveness of interceptive approaches. We also believe that minor midline changes in the lower arch is of less importance for the patients as studies have shown that even a few millimeters of deviation in the upper arch often go unnoticed by both laypeople and orthodontists.

We also want to address the theory that the mesial root of the second primary molar could act as a “book-end” and thus prevent distal movement of the more anteriorly positioned teeth. This is difficult to comprehend unless the tooth is ankylosed. Under normal conditions, the mesial root is just as movable as other roots when subjected to force. It is unlikely that it alone would prevent movement of incisors, canines, and molars—especially since spontaneous distal movement is rarely observed in these regions. Although clinical experience plays an important role in decision-making, it is essential that our recommendations are based on evidence that extends beyond individual outcomes, case series. This is where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) become valuable. They allow us to test clinical assumptions and establish whether a given procedure is generalizable and broadly applicable. Hemisection involves higher cost, more visits, and increased discomfort for the patient. If we are to recommend such a method, we must ensure that it is supported by well-founded and strong evidence. A well-designed RCT involving unilateral agenesis cases could offer that clarity. Until then, simple extraction remains a more efficient and evidence-based approach.

Kevin O’Brien final comments?

This discussion effectively illustrates the practical dilemma where research evidence does not always align with the clinical experience of some. There are many examples of this in orthodontics, which is why we need carefully considered RCTs such as the one being discussed here. However, no RCT is perfect and one of the key difficulties with evidence-based medicine is that it can be challenging for experienced clinicians to accept research findings if they conflict with their own clinical experience.

This is why we should never forget that evidence-based orthodontics is predicated on the balance between clinical experience, high-quality research, and patient preferences.

When I considered the findings of this trial, I was initially concerned that it was only relevant to bilateral agenesis. However, I found its findings very useful as they raised questions about unilateral management. It was also interesting to observe that patients experienced more difficulties with the hemisection approach. Furthermore, there is uncertainty about whether unilateral loss of the primary second molar will always cause a midline shift. Importantly, despite these uncertainties and the results of this study, I would be inclined to follow its conclusions and consider extraction, hoping that any midline shift would be minor and correctable in definitive fixed appliance treatment.

I would explain this to my patients and let them make the decision. In this respect, this study is very valuable.

Emeritus Professor of Orthodontics, University of Manchester, UK.