A really useful paper on intercepting the palatally displaced canine.

We all try to intercept the impaction of a palatally displaced canine. This new paper was written to provide general dental practitioners with information about this treatment. Its contents are very relevant and helpful for both general practitioners and orthodontists.

Interceptive treatment aims to improve the position of the PDC and ideally enable its eruption without treatment. To achieve this, patients with suspected PDCs must be referred and treated early.

A team from London, South of England, and Zurich, Switzerland wrote this open-access paper. The British Dental Journal published it.

Martyn T. Cobourne, Jadbinder Seehra and Spyridon N. Papageorgiou

BDJ 239, pages 463–470 (2025).

What did they ask?

They wanted to provide information on

“The early diagnosis, appropriate referral and current evidence-based related to simple interceptive management of PDCs”

What did they do?

They wrote a clear narrative review. Importantly, they also re-analysed data derived from previous systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials. This is where the paper becomes interesting.

What did they suggest?

Identification

The first part of the paper discussed the routine assessment and monitoring of the eruption of the permanent canine. This reflected the current practice of palpating buccally when the child is 8-10 years old. If the canine is not palpable, then they should take relevant radiographs to investigate further. These views should be periapicals and/or dental panoramic views. Importantly, they felt that the routine use of CBCT for the initial diagnosis of these teeth was not indicated because of the significantly higher dose compared to periapicals. They proposed that more complex views, such as CBCT, be performed by the specialist orthodontist if necessary.

Interception

The basis for interception is creating space. This can be achieved by extracting the primary canine and/or performing maxillary expansion. However, they suggested that the evidence supporting this is unclear and difficult to interpret.

I found this comment interesting and examined their sources carefully. They initially considered the most recent Cochrane systematic review. I have discussed this before. Here, the evidence was rated as very uncertain. This was due to unclear trial conduct, variations in study design and primary outcomes, and inconsistency in participant selection. This is a concerning conclusion, and they clearly explained the reasons behind it. They also pointed out issues with several publications often cited as evidence for the beneficial effect of primary canine extraction.

The paper by Ericson and Kurol. This was published in 1988 and is regarded as a ‘classic”. This retrospective study provided us with helpful information for that time. Nevertheless, we need to consider that this study did not include an untreated control group. Similar issues were evident in a further study led by SuePower in 1993. As a result, there remains a significant degree of uncertainty regarding the conclusions of these two studies.

A group led by Tiziano Baccetti published two related randomised trials in 2004 and 2008. However, their reporting lacked clarity; most PDCs were in favourable positions, and the groups were unbalanced. As a result, these papers were not included in the Cochrane review that examined this treatment.

Further trials by Bazargani reported that removal of primary canines was effective. However, the trial was small and potentially lacked pre-treatment equivalence.

Finally, in 2015, Nuamova reported the papers on her trial. They showed that in the primary canine extraction group, 69% of PDCs erupted compared to 39% of controls. I have previously posted about this trial. However, there are some issues with this study. These concerns relate to some patients having bilateral impactions and others having unilateral impactions. Importantly, the observation period for eruption of the PDC was set at 2 years, but the primary canine was extracted after one year in the control group. While these issues are valid, this remains the best study we currently have evaluating the interceptive effect of removing the primary canine.

The authors of the present paper then carried out a detailed literature search. They identified five RCTs on the effect of removing the primary canine. These were by Baccetti, Bazargani, Baccetti, Willems, and Naoumova. They then requested the raw dataset from the teams. They could not include the papers from Baccetti because he is sadly deceased. Two of the trials provided them with data, and one supplied data adjusted for clustering. The team then re-analysed the data to account for clustering and conducted the relevant meta-analysis.

What did they find?

I will only include the data on the evidence regarding the extraction of the primary canine. They found that

When they analysed the studies of Naoumova this showed that

- Eruption of the permanent canine was significantly lower when close to the midline.

- Extraction of the primary canine was associated with improved eruption odds of the PDC. The odds ratio was 3.5 (95% CI=1.4-8.9, p=0.008).

When they looked at all five studies, the results were slightly different.

- Extraction of the primary canine was associated with increased eruption odds. The odds ratio was 3.6 (95% CI=2.2-6.2).

Their overall conclusion was

“Current data suggests that PDC eruption following interceptive extraction of the primary canine is unpredictable”.

They went on to suggest that data from the trials indicate a potential benefit from interceptive extraction. However, we are uncertain about treatment timing, which patients are likely to benefit, and which displacements are likely to respond most favourably.

This led them to conclude:

- We could extract the primary canine if there is root resorption of the primary canine when the patients are between 7.7 and 14 years.

- Extracting the primary canine beyond 14 years is unlikely to be successful.

- The closer the PDC crown is to the midline, the reduced chance of success.

- The success of this intervention is unpredictable, but a favourable outcome can be achieved if treatment is commenced between the ages of 10–13 years, the patient is in the mixed dentition, there is space for the permanent canine within the dental arch, and radiographically, the permanent canine crown is not close to the mid-sagittal plane/midline.

What did I think?

This is a valuable paper for anyone concerned with monitoring the transitional dentition and attempting interception of PDC. It provides clear and sound advice on the timing of any extractions. It is open access, allowing orthodontists to circulate it to their referring dentists.

This paper was also interesting from a research point of view. It was refreshing to see a paper that deviated from the typical orthodontic systematic review, bogged down with meta-analyses of multiple outcomes, and concluding that we need more research.

It was also important to see a re-analysis of the trial data, and it was great to see that the authors of the papers were open to allowing this re-analysis.

I realise that all readers of this blog may not be familiar with odds ratios. As a result, it is worth exploring the findings.

The odds ratio (OR) measures the strength of association between an exposure and an outcome by comparing the odds of the outcome occurring in an exposed group to the odds of it occurring in a non-exposed group. An OR of 1 means there is no association, an OR greater than 1 indicates the exposure increases the odds of the outcome, and an OR less than 1 indicates the exposure decreases the odds.

If we look at the data in this paper, the odds ratio for the successful eruption of the PDC was 3.6 (95% CI=2.2-6.2). This means that when we extract the primary canine, the odds of successful eruption of the PDC are 3.6 times higher than when we do not extract the primary canine. However, you also need to consider the confidence intervals. These are wide, indicating that the OR may range from 2.2 to 6.2. This reflects the uncertainty in the data. This may have occurred because of the variation in the position of the PDCs. From this, we can conclude that removal of the primary canines, on average, results in a wide range of successful eruption of the PDC.

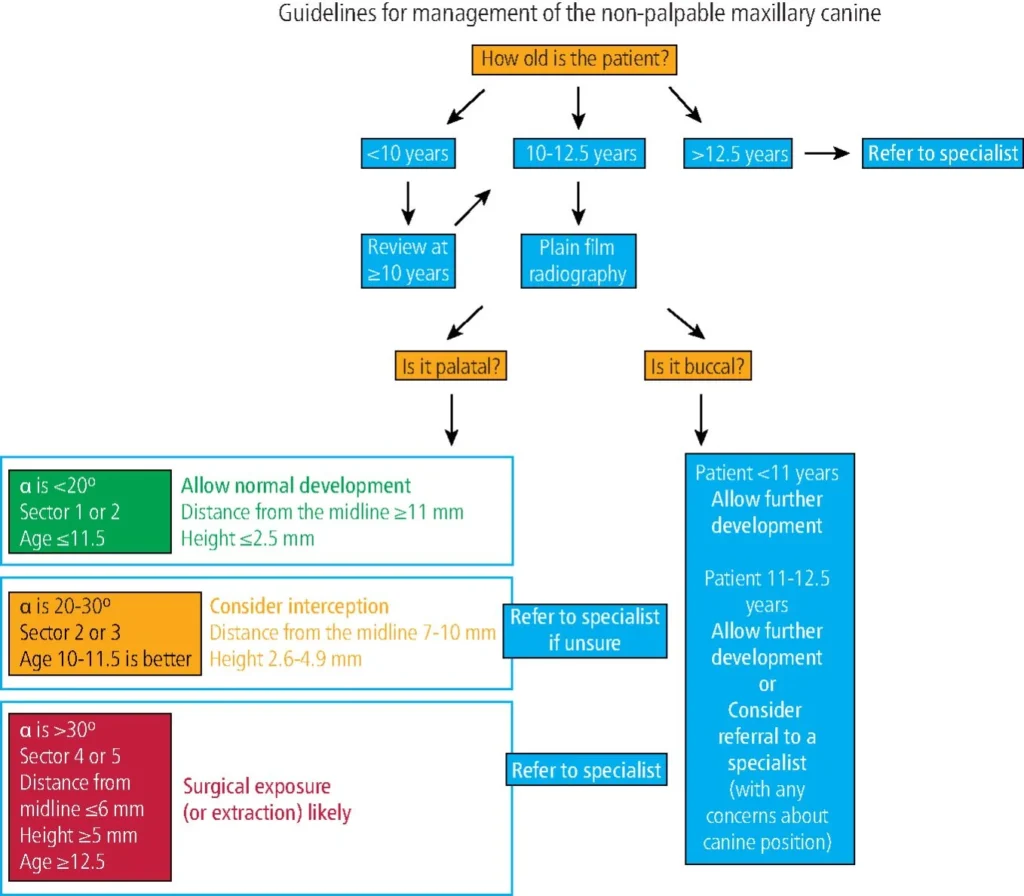

The authors also included an excellent flow chart providing guidance for the general dental practitioner on the management of canines in their paper. They have sent me a copy and I have included it here. This explains how the data influences their decision-making on the extraction of the primary canine.

This also summarises my final thoughts on this useful paper. As is common in orthodontics, the situation remains somewhat unclear, and personal clinical experience and patient wishes should be considered.

Emeritus Professor of Orthodontics, University of Manchester, UK.