Back to Basics. Myth and Reality: Interceptive management of ectopic canines

The alignment of ectopic canines is one of the more challenging treatments we encounter as orthodontists. In one sense, these patients present a ‘perfect storm’ often having good alignment and a reasonable occlusion, limiting the aesthetic benefit of treatment. In addition to lengthy treatment, complications and outright failure is a real risk. This is particularly true in older patients with more displaced permanent canines. Therefore, the advantage of effective interception to circumvent the need for appliance-based alignment is clear. A range of possible interventions have been touted to redirect ectopic canines. However, the solid evidence seems to support just one of these.

What is the evidence?

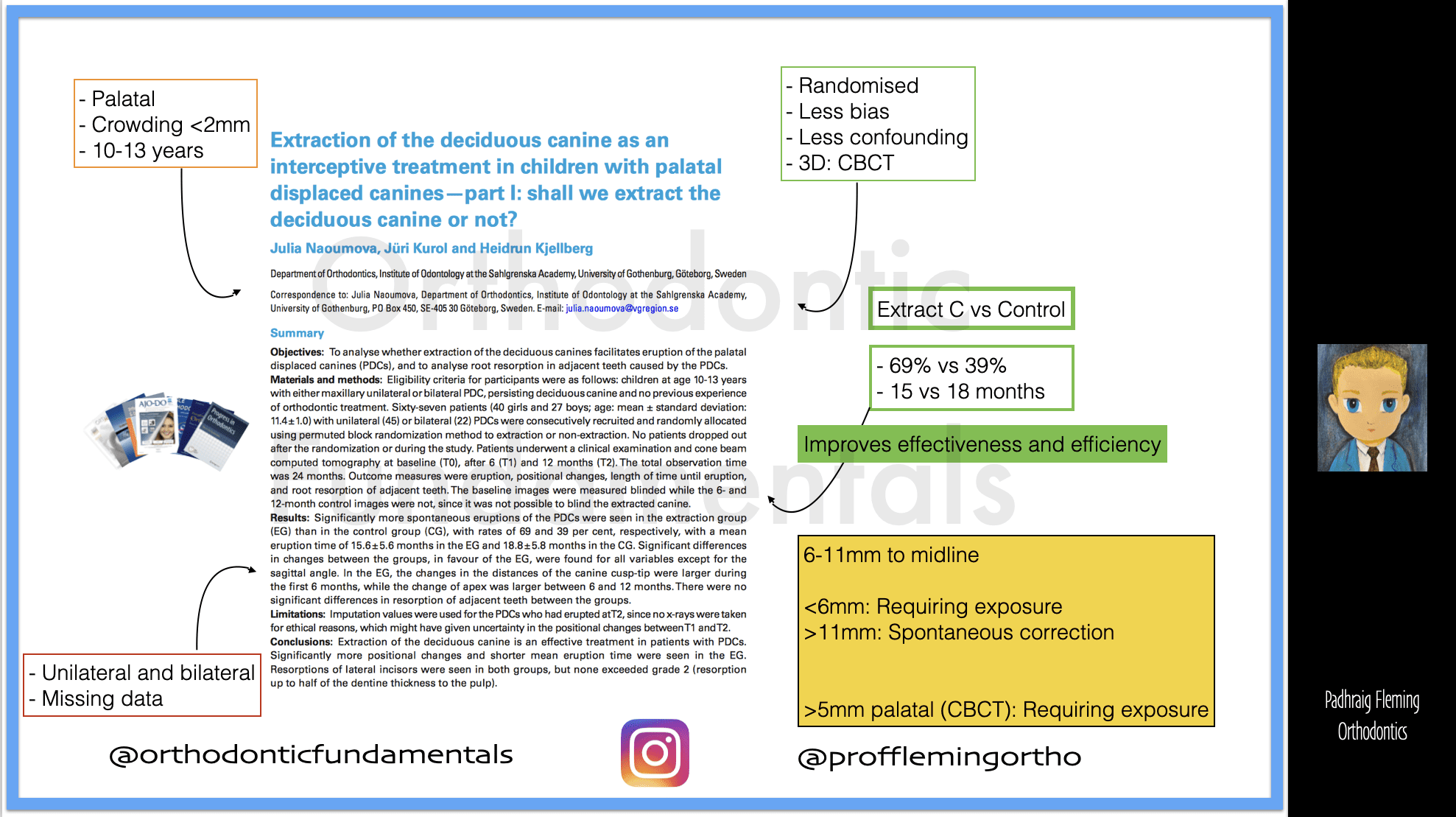

The evidence underpinning the removal of primary canines to improve the position of the underlying ectopic canine is reasonably strong. In particular, the classic research by Ericsson and Kurol highlighted an improvement in 78% of cases (64% or 91% pending on the degree of ectopia) in uncrowded 10-13- year-olds over a 12-month follow-up period. Unfortunately, this study lacked a control group. Furthermore, it was also confined to uncrowded cases and lacked three-dimensional evaluation.

A more recent randomised controlled trial included a control group (involving supervision only), providing further support for the benefit associated with primary canine removal. In particular, 69% of canines in the intervention group improved vs. 39% in the control. Eruption occurred more efficiently with removing the primary canine (15 vs 18 months). It was also notable that it took 18 months or more for some permanent teeth to erupt. On this basis, I recommend removing primary canines in most cases in this age range. I tend to re-evaluate 12 months following interceptive extraction. However, I am now a little more patient than I once was in giving the canines time to improve. It is also important to note that some canines do improve spontaneously.

Equally, some important prognostic indicators were observed based on Nauomova’s second paper. For example, using CBCT-derived data, adjacence to the midline may be necessary, with those less than 6mm from the upper midline likely to require exposure, while an ectopic canine having its tip over 11mm from the upper midline may be destined to improve spontaneously.

Other procedures?

A range of additional procedures has been claimed to confer extra benefit (beyond that associated with primary canine removal). These include:

- Expansion (with RPE or a quadhelix)

- Double extraction (Cs and Ds)

- Space maintenance (TPA)

- Molar distalisation (Cervical-pull headgear)

Do these supplemental interventions work? Well, based on anecdotal evidence, they may. However, these ‘apparent successes may occur naturally or be prompted by the loss of the primary canine only. Clinical research broadly does not support the use of these additional interventions. These were summarised in the excellent Cochrane review (Benson et al., 2021). A number of the primary studies either lacked methodological rigour or had inconsistent findings. For example, one trial pointed to an advantage associated with double extraction. At the same time, a more recent, well-designed study reported a higher percentage of canines erupting in the single extraction group (78% vs 64%).

Conclusions

Is it fair to conclude that removing a primary canine is the only proven procedure for redirecting ectopic canines? It probably is. As a result, we should only consider these supplementary procedures if there is a separate indication, e.g., transverse maxillary constriction warranting rapid maxillary expansion. I will caveat this with the possibility that timing may be influential. Conceivably, ectopic canines may respond differently if early diagnosis and expansion (in patients less than 10) are undertaken. However, given the unpredictable nature of canine eruption and response, we are much more likely to subject younger patients to unnecessary treatment if we take this more proactive approach. Either way, further research is needed to support this contention or disprove my reticence.

This post was originally published on the Orthodontic Fundamentals Page.

Professor of Orthodontics, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Ireland

It has been documented in the orthodontic lecture that one etiology of canine impaction is physical obstruction , which could be the granules of severely caroius primary tooth. The study looked at extraction of primary canine didn’t clarify if the primary canine had a periapical lesion. Therefore interpretation of this data should be causion.

The unique criteria of malocclusion associated with canine impaction should be analyzed carefully when reflecting on any upcoming clinical trails.

Dear Prof. Fleming

While a definitively diagnosed maxillary skeletal transverse deficiency ( a.k.a., TMC-transverse maxillary constriction) has not yet been shown to be a causative factor in the development of ectopic canines, it (Dx:skeletal TMC) is indeed a very frequent co-morbidity with sub-optimal canine eruption per se. And, as skeletal TMC in the deciduous/early mixed-dentition, with or without the presence of a posterior dental cross-bite, will seldom, if ever, self-correct, usually worsen, and often become co-morbid with sleep-breathing disturbances, lowered QOL, and often blocked out and/or ectopic permanent canines, what might be factors precluding an orthodontist from diagnosing and recommending treatment of skeletal TMC in young/very young (under 72 months old) patients?

Thank you for considering.

Slainte!

KEV