When should we take Cone Beam CT of the orthodontic patient?

Following on from last weeks post about CBCT and childhood cancer. This is a guest post by Alex Ditmarov on when should we be taking a Cone Beam CT of a child.

Alex first published this on his own blog. I thought that it was good and he has allowed us to re-publish this here. I thought that he has put together a really nice summary of an evidence based approach to taking CBCTs on children.

As an aside, I think that his blog is great and it is well worth reading

“When should we take Cone Beam CT of the orthodontic patient?”

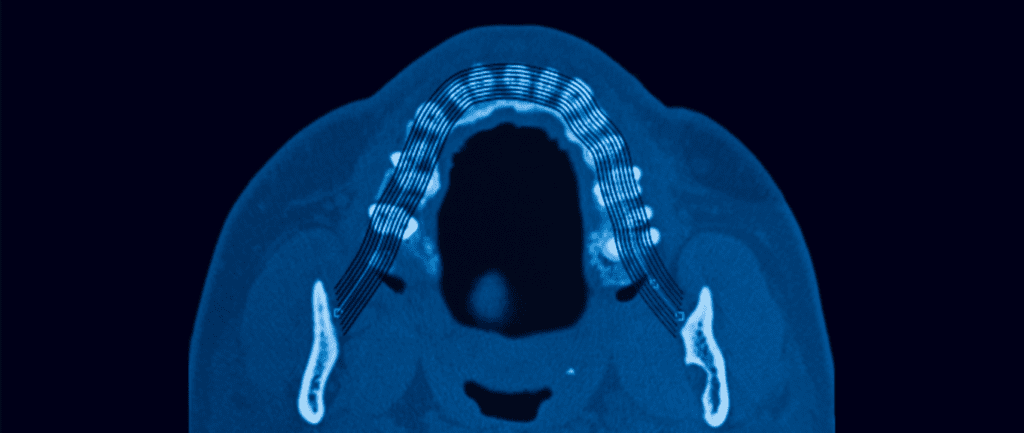

How many times online or during a conference, have we seen a practitioner advocating for the routine use of CBCT? To justify this, the orthodontist often shows the images of scanned airways or primary dentition before and after and say.

“3D images helped me to diagnose airway constriction and crowding. I can’t even imagine how I would now practice without this marvellous technology!”

These, of course, are strong statements and if you look closer, you may find an affiliation of the practitioner with the manufacturer of diagnostic equipment.

So, when should we take a CBCT?

Does Cone Beam CT affect clinical decisions?

First, I want to look at a study in which 24 orthodontists were asked to evaluate six patients cases with classic diagnostic records and then added CBCT records to the collection of records. They measured the consistency of the examiners treatment decisions with and without the CBCT.

Impact of cone-beam computed tomography on orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning

Ryan J Hodges et al., Am J Orth, 2013 May;143(5):665-74

DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.12.011

They found that the orthodontists did change some of their treatment plans. Importantly, it was in these particular situations:

- Discovery of unexpected aspects of the location if unerupted teeth

- Severe root resorption related to contact of the crown of an unerupted tooth with an erupted tooth

- Severe skeletal discrepancies

Importantly, the availability of Cone Beam CT records did not influence the clinical decisions on airway or crowding.

The authors concluded:

“We propose that CBCT scans should be ordered only when there is clear, specific, individual clinical justification.”

Of course, it is a slightly dated and small study. However, more recent and extensive studies only reinforce its findings. For example, I advise you to look at this comprehensive systematic review from 2018:

Annelore De Grauwe et al., EJO, Vol 41, Issue 4, Aug 2019

DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjy066

The advantages of CBCT over 2D imaging proposed by the authors were:

- Diagnosis of root resorption

- Evaluation of root fractures

- Imaging of complex craniofacial problems

Is CBCT a reliable method to diagnose airway problems?

Here is another relevant study that looks particularly at the airway assessment:

Cone-beam computed tomography airway measurements: Can we trust them?

Daniel Patrick Obelenis Ryan et al., Am J Orth, 2019;156:53-60

DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.07.024

Despite the unambiguous message of the AAO white paper on sleep apnea, some practitioners still use CBCT pictures to illustrate the effects of their treatment in enhancing breathing.

The issue with this approach is the fact that the airway is not static. It continually changes during the breathing cycle, and a radiographic image depicts just a particular stage of the process.

The authors included 27 CBCT scans of non-growing patients taken with 4-6 months intervals in their study. One trained operator did all the measurements.

The authors concluded:

“Different CBCT exams with equal scanning and patient positioning protocols can result in different 3D pharyngeal airway space readings.”

In other words, every time you take a CBCT scan, the airway volume measurements would be different.

Low dose CBCT?

Indeed, one of the most critical issues of CBCT is its radiation dose. To the day, the effective dose of CBCT scans produced by most machines is many times greater than conventional panoramic examinations.

However, some adepts of routine CBCT examinations state that there is also an option to take low dose CBCT, comparable to panoramic radiographs.

After a PubMed search, I found a paper where the authors indeed claim one particular CBCT machine model is capable of producing extremely low doses.

Phantom dosimetry and image quality of i-CAT FLX cone-beam computed tomography

John B. Ludlow, Cameron Walker, Am J Orth, 2013 May;144(6):802-817

DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.07.013

This study’s issue is that the manufacturer paid the authors an “honorarium” – the exact sum is not disclosed. Furthermore, despite the potential positive bias, the authors’ conclusion was still not very persuasive:

“QuickScan+ effective doses are comparable to conventional panoramic examinations. Significant reductions in image quality accompany significant dose reductions. However, this trade-off may be acceptable for certain diagnostic tasks such as interim assessment of treatment results.”

In other words, we probably could limit the dose using a piece of expensive new equipment, however no guarantee we will be happy with the images produced.

When should we take CBCT of the orthodontic patient?

Overall, there is no data in the literature to support the indiscriminate use of CBCT in orthodontic diagnosis. We certainly know that CBCT has dramatically expanded our visualisation abilities, but we also have to consider the potential harm of the radiation.

Given the current research data and my clinical experience, here are the situations I take a CBCT scan:

- Impacted and supernumerary teeth

- Root resorption evaluation

- Placement of TADs

- Visualisation of TMJ structures if problems suspected

- Midpalatal suture maturation assessment

- Surgical cases

No doubt in the future, we will have new CBCT machines with proven low radiation doses, but until then, we should not put our interests above the patient’s safety.

Emeritus Professor of Orthodontics, University of Manchester, UK.

Great follow-up, thank you!

This post is silent on use of CBCT to make custom therapeutic agents, which is not a diagnostic function, but an additional role of improvement of therapy, by customising therapeutic agents. Custom-made robot bent super-elastic NiTi wires will deliver super accurate crown positions, and also deliver super accurate and better informed root positioning, getring away from collisions with obstacles such as collision with other roots, and in particular collision with cortical plates.

There is published evidence of about 7 papers, albeit low level papers, that all concur that by using this more accurate system for individual customised tooth positioning of crown and roots, that treatment times are reduced on average by 35% to 40%. It’s not due to or claimed to be acceleration of movement, it’s due to precision f movement to target positioning, eliminating need for round tripping and introducing finishing at start to treatment, because the wires are fully programmed and finished at the *beginning* of tooth movement.

The studies were all done by postgraduates in university courses in USA and mostly done in the hands of inexperienced or trainee orthodontists. With more experienced orhodontists, the knowledge could be different. In particular, perhaps other factors, like intermaxillary corrections greatlt affect time in treatment.

Making customised NiTI arxhwires by robots is a 30 years old technology. But using CBCT data for the manufacture of therapeutic wires is it about for about 6-8 years old. I have used the system for 10 years.

This system itroduces lingual braces as an everyday routine way of doing braces, (but only if you combine self lighting lingual braces!).

If low dose or even medium dose CBCT is used for therapy as well as for diagnosis, and it’s use cuts off up to a third off treatment time in the majority of simple cases, how is the cost benefit analysis considered? Is the risk of cancer in the whole population to high to use therapeutic radiation in our particular form of Dentistry?

This is a question for ethicists and philosophers, it’s more akin to a religious question, rather han one that scientists can answer easily.

May we say, for example, to the individual:

“If you are willing to take the risk, if you are willing to absorb the amount of ionising radiation that you’ll get by living another two weeks on this green planet Earth, or of you are willing to absorb what you may absorb in gamma rays while flying to Australia next Year to come to the best ASLO lingual meeting in rhe great city of Melbourne, and you absorb that radiation in exchange for a faster, better quality orthodontic outcome, will you accept that radiation risk?”

My clients are very educated, people; doctors, dentists, lawyers, professors. They say “Yes”.

Is this wanton disregard for public health and pedalling of misinformation?

Best from Geoff.

Regarding the Ludlow article,

Here is a link to the full text of the Ludlow article https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3914004/

If you look at the free text of the paper in pubmed you will see that the research was actually funded by the National Institute of Health.

It was very honest of Dr. Ludlow to disclose that there was a travel support honorarium, meaning whatever it cost to travel to the location of the unit. When you test as many of these units as he does, the travel costs can be quite burdensome.

There seems to be some skepticism regarding the accuracy of the data presented in the paper. I would invite Alex to contact the authors if he would like more information.

Cheers, Cameron Walker

Cameron,

Was there any particular reason that there wasn’t an attempt made to use the novel phantoms from your study to look at the dosimetry from a 2D panoramic/ceph machine, as was done in the comparative study below which your paper references?

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22464525/

Hi Cameron, thanks for the details. Sorry if my remarks on the ‘honorarium’ sounded unreasonably harsh. I just think that we always should be paying attention to potential conflicts of interest. And this is great that Dr. Ludlow disclosed his. However, I guess what is more important here is his conclusion: “Significant reductions in image quality accompany significant dose reductions.”

Best regards, Alex

The points made by Dr Wexler are also valid in the sense that virtual (surgical) treatment planning is heavily reliant on 3D scans. I have been invited to author a review on this subject, hence my interest in this and related threads. Not sure if I’m gonna accept, as yet since

Dr Walker also makes a telling comment on the nature of the discussion. I don’t mind a healthy degree of skepticism but I draw the line at cynicism. For example, “The issue with this approach is the fact that the airway is not static. It continually changes during the breathing cycle, and a radiographic image depicts just a particular stage of the process” What’s the big deal? We need to correct for the phase of the respiratory cycle and use known physiologic endpoints (e.g. Singh GD, Olmos S. Use of a sibilant phoneme registration protocol to prevent upper airway collapse in patients with TMD. Sleep Breath. 2007;11(4):209-16). I am sure there are better articles on the subject but to say that “every time you take a CBCT scan, the airway volume measurements would be different” is misleading, is not surprising and is no different from other physiologic phenomenon e.g. a blood pressure reading taken at different times of the day (and night) will differ. Moreover, sleep physicians are already aware that home sleep apnea tests tend to underestimate the severity of the condition compared to polysomnography – so should we simply discard HSATs as well as CBCT scans and rely on 2D cephalometry to prove that orthodontists cannot grow mandibles, etc?