It’s nice to see some sense about mouth breathing and orthodontics

This post is by Martyn Cobourne, who condenses his views on orthodontics and mouth breathing. He counters some of the nonsense we are currently seeing in orthodontics.

Introduction

A really excellent editorial by Sanjivan Kandasamy just published in the AJODO this month: dismantling some of the myths associated with breathing, posture and facial growth. I particularly like the discussion of the often quoted but experimentally flawed ‘classic’ papers by Linder-Aronson and Harvold investigating adenoidectomy in children and forced-nasal breathing in monkeys, and their extreme effects on facial growth and induction of the ‘adenoid face’. I would argue that the questionable findings of these investigations have been further demonstrated by systematic reviews failing to show extremes of facial growth in association with mouth breathing or indeed, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) as reported by Katyal et al, 2013; Fagundes et al, 2022; Finke et al, 2023).

The onslaught of airway orthodontists

The tsunami of orthodontists claiming that orthodontic management of mouth breathing and sleep disorders in children through early maxillary expansion, functional appliances and myofunctional therapy is seemingly never-ending. These strategies are advocated through opinion articles, conference presentations and poor research. The evidence that maxillary expansion at any age can induce significant anatomical (and more importantly) physiological effects on the airway is low-quality and unconvincing as found by Buck and also Niu. Indeed, there is a better evidence base showing that functional appliances do not induce clinically significant additional mandibular growth, whilst the evidence relating to myofunctional therapy is almost non-existent. Anyone interested in the complex subject of mouth breathing, airway and indeed, OSA should make the excellent AAO guidance on orthodontics and management of OSA mandatory reading.

Oversimplification of theory

The problem with any theory that ends in excess is that it over-simplifies the reality – particularly in relation to biology. Whether you claim to be an ‘airway orthodontist’, or ‘airway dentist’ (heaven forbid), believing that the oro-facial environment is entirely responsible for abnormal facial growth and development – be that incorrect tongue posture, nasal breathing or some combination of the two, ignores the fundamental importance of genetics.

A genetic example

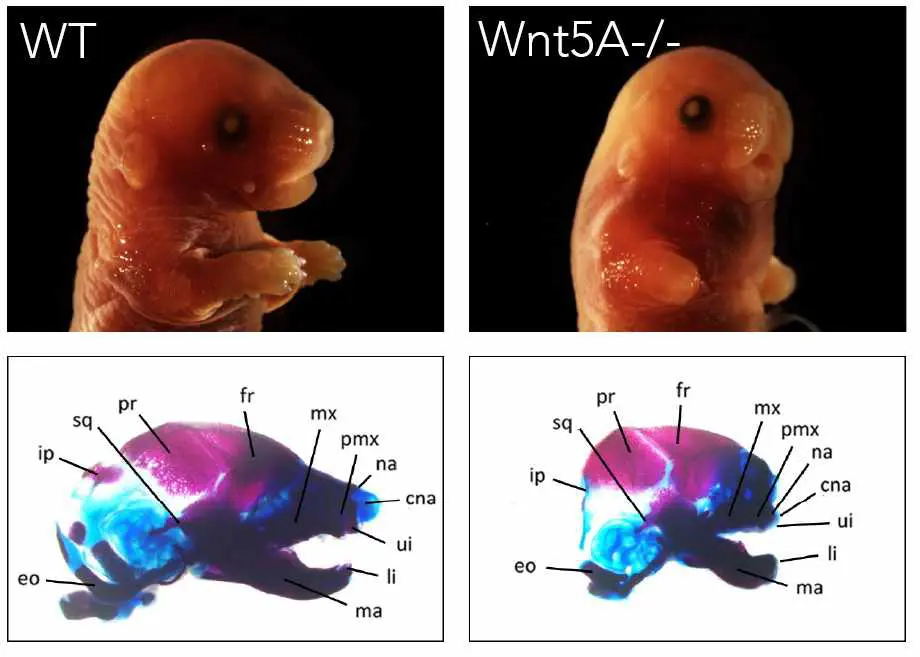

I thought it would be useful to use some images of a mouse line we are currently studying in our laboratory.

One is a wild type (on the left) and one is mutant for a gene called Wnt5A (many thanks to Daniel Stonehouse-Smith for the images). The nature and function of the protein encoded by this gene is not important, but without this single functioning gene, the craniofacial phenotype (and indeed, the limb phenotype) of these mice is significantly disrupted, clearly demonstrated in the craniofacial region by the truncated maxilla and mandible. The environment does not cause this, it is primarily the result of genetic background and demonstrates the huge influence of genetics and gene function on craniofacial development.

Some clinical common sense is required

Clearly, the environment is also important for normal craniofacial growth and development; nobody would deny this. There may well be a role for adjunctive orthodontic therapy in the multidisciplinary management of breathing disorders, nobody is dismissing that. However, craniofacial growth and development represents a complex inter-relationship between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. The sooner we accept this and cease making claims based on questionable evidence or fantasy, the less our patients will be misled, unnecessarily treated, or even harmed. This editorial is an excellent reference point for anybody interested in sensible further reading on this unnecessarily controversial subject.

I love the embryology/genetics example! Such a solid example of the “nature” aspect of the nature/nurture debate is a refreshing addition into discussions that are usually just heated opinion….

As a paediatric ENT that manages sleep disordered breathing, I have some concerns about the claim made here.

For starters- the mouse model. This doesn’t actually prove anything other than a certain genetic manipulation can lead to a certain outcome. The extrapolation made to somehow assert a claim is not overly accurate.

The next issue to take to task is the very flawed article cited first up. In the day and age we can use our AI machines to appraise the accuracy of things, and this one comes out very poorly. One no longer needs to have a professor title or PhD (of which I have both) to be able to decipher claims made.

The reference to research back in the 1970s without acknowledging papers coming out in the past few years supporting the same is selection bias to suggest all that has come out are refutations.

And it may be prudent to revisit the pubmed search of “myofunctional therapy” because to say there is no evidence is to once again be less than honest about what is indeed published.

This ongoing quest to divorce mouth breathing from orthodontics is still a pointless exercise. Regardless of whether mouth breathing does or does not impact jaw growth does not detract from what the focus should be- that the child can’t breathe properly, that they are at high risk of sleep disordered breathing, and that they should be referred immediately to an ENT rather than trying to tell parents that it’s nothing to worry about.

Thanks for your comments, I will answer them. I think that you are approaching this discussion from an ENT point of view, which is exactly the correct approach. As a result, there is nothing wrong with your overall message. Howvever, I and other are concerned with what appears to be the ever increasing number of orthodontists and dentists who label themselves “airway” experts and state that orthodontics plays a major role in treatment. As research shows us, there is a lack of evidence that orthodontic treatment influences the airway. Unless, we have missed something. However, if you can reference a RCT that shows a meaningful effect, that would be great. Finally, I think that Martyns concluding comments do agree with you? I have pasted them here….”There may well be a role for adjunctive orthodontic therapy in the multidisciplinary management of breathing disorders, nobody is dismissing that”. Best wishes: Kevin

What would ENT do for them in terms of investigations and differential diagnoses and treatment options?

Stephen Murray

Swords Orthodontics

The title is designed to be disruptive, and it certainly invites debate. But in trying to frame the argument as a matter of “sense” versus “nonsense,” it risks flattening a subject that is far more complex and dynamic.

Craniofacial growth is not dictated by genetics alone, nor is it simply the result of environment. Development is shaped by the interplay between the two, mediated through epigenetic regulation. Epigenetics is where breathing mode, posture, and function can alter gene expression and redirect growth vectors. To emphasise genetics as the dominant driver without considering these regulatory pathways is to overlook a central truth of developmental biology: adaptation is written into the system.

This matters clinically. The use of a Wnt5A knockout mouse as a model is scientifically valid in a narrow sense, but it cannot be equated with the polygenic, multifactorial reality of human growth. A single-gene deletion that produces severe craniofacial deformity shows what happens when development is catastrophically disrupted, not how normal growth adapts in the presence of subtle environmental pressures. Such examples confirm that genes matter, but they do not negate the influence of airway function, nutrition, or neuromuscular activity on everyday growth trajectories.

Equally problematic is the sweeping dismissal of airway-related orthodontic interventions as “low-quality and unconvincing.” That wording does not appear in the systematic reviews that are cited; it is an interpretation. Reviews can only reflect the limitations of the available studies. The absence of high-level evidence is not evidence of absence. In fact, there are now longitudinal data showing measurable benefits in airway parameters following interventions such as maxillary expansion. The correct position is not to deny plausibility but to call for better-designed trials to explore these effects more rigorously.

What is missing in the current debate are the principles of compensation and adaptation. Adaptation describes the way bone, muscle, and soft tissues remodel under altered functional demands—such as the craniofacial remodeling that accompanies chronic mouth breathing. Compensation describes how dysfunction is masked, often for years, by structural or behavioural adjustments, until the system can no longer sustain equilibrium. Without these principles, we cannot explain why some children with airway compromise develop dramatic skeletal changes while others appear “normal” until their compensatory reserve is exhausted.

It is equally misleading to imply that only extreme morphologies, like “adenoid face,” are clinically relevant. Airway compromise can have profound consequences long before gross deformities appear. The earliest signs may be subtle shifts in growth vectors, changes in tongue posture, or altered head position. These small deviations matter, because they accumulate over years and determine how growth potential is ultimately expressed.

Interestingly, Edward H. Angle himself recognised this. If you read his original 1899 paper, you will see that he linked occlusion with breathing and development. Yet his followers did not carry these ideas forward. The Angle Society chose instead to preserve only the static molar-based scheme.

Why did this happen? Because functional aspects such as airway and growth were recognised but not easily measurable with the science of the time. Molar relationships were simple, visible, and reproducible. They could be taught, tested, and institutionalised. That made them attractive, even if it meant sacrificing complexity for clarity. In seeking legitimacy as a new specialty, orthodontics codified what was simple and measurable while leaving aside what was functional and dynamic.

That decision gave us a common language, but it also narrowed the way our field viewed malocclusion for more than a century. The persistence of Angle’s categories in teaching and research is not evidence of their validity—it is evidence of institutional inertia.

Where does that leave us today? It leaves us with a choice. We can continue to reduce airway discussions to polemics about “sense” and “nonsense.” Or we can build a more nuanced conversation that integrates genetics, epigenetics, environment, and function. We can acknowledge that evidence is incomplete without pretending that incompleteness equals irrelevance. And we can reclaim compensation and adaptation as the keys to understanding why growth outcomes vary so widely across individuals.

Angle gave us a language. But if orthodontics is to remain relevant in the 21st century, we must now give ourselves a compass—one that points toward a systems-level understanding of growth, development, and airway.

Oh where is Dr. Melvin Moss when we need him??

Thank you for your deep and wise comment. Not many of them.