TADs or surgery for correcting AOBs: More or less stable?

The advent of TADs and 3D printing has heralded a new dawn in orthodontic mechanics. Many of these approaches are a little more involved. I have previously discussed the relative invasiveness of various treatment modalities in modern-day orthodontics. As is often the case, Peter Greco puts it better than anyone else. In one of his articles in the AJO-DO: ‘Before we initiate treatment, we must ask ourselves if the appliance is clinically effective, whether the risk-benefit ratio justifies our choice, and if less invasive intervention would equally meet our objectives’.

Undoubtedly, the predictable use of TADs has been a fantastic outlet. In particular, their use in avoiding more invasive or onerous treatment is a step change for the specialty. I can think of situations where TADs can produce better orthodontic outcomes with less long-term implications- avoiding the need for prosthetic replacement(s) in hypodontia being an obvious one. However, we increasingly owe it to our patients to ensure that we are proficient in using these mechanics.

But could TAD-based intrusion be as stable as a surgical intrusion of the posterior dentition in patients with anterior open bite? If the answer is ‘yes,’ this might suggest significant ‘added value’ with TADs in the right patient.

The authors of this retrospective study aimed to address this possibility. The study was performed in South Korea and was published in Clinical Oral Investigations.

Pi En Chang, Jun‑Young Kim, Hwi‑Dong Jung, Jung Jin Park, Yoon Jeong Choi

Clinical Oral Investigations:2022 doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04615-6.

What did they do?

The authors compared the posttreatment stability of anterior open bite (AOB) correction following either TAD-based molar intrusion or bimaxillary surgery. They did a retrospective follow-up study of 42 patients.

Inclusion Criteria:

Skeletally-mature participants in the non-surgical group had AOB correction by the intrusion of the maxillary molars using miniscrews. They had no significant mandibular asymmetry. They matched this cohort of patients to subjects treated with bimaxillary surgery to address an anterior open bite.

Methods:

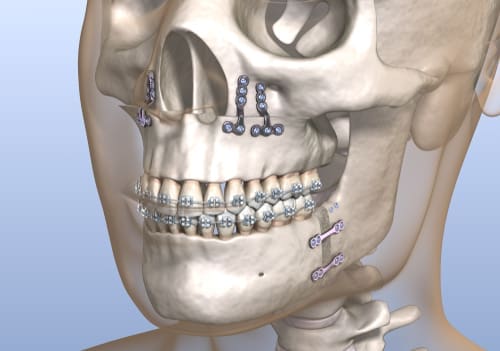

The clinicians did the TAD-based molar intrusion with paired palatal and buccal TADs on each side (eight overall). They attached elastomeric traction to these. They did not use trans-palatal appliances. The study team attempted to match the smaller (n= 21) sample of non-surgical cases with a subset from a larger cohort of surgical patients (n= 58). In the surgical group, the 2-jaw surgery involved a Le Fort I osteotomy with maxillary impaction and either sagittal split osteotomy or intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy.

They measured stability using cephalometric parameters only with radiographs taken pre-treatment, following molar intrusion (or surgery), at debond, and during retention. The mean period of posttreatment follow-up was approx. 34 months.

What did they find?

Both treatments successfully corrected the initial open bite (of 3.2 to 3.6mm), with the overbite increasing by 4.5 to 5.1mm with treatment. This change was primarily due to maxillary molar intrusion (of 3.3 mm). They saw a small amount of AOB correction relapse before debonding (0.5 to 0.9mm) either following surgery or after TAD-based intrusion.

Overall, approx. ¾ (77-79%) of AOB correction was retained over the 34-month follow-up period with no significant difference in the magnitude of change between the groups. When they looked at posttreatment relapse. They found that the maxillary first molar moved 1mm and 0.4mm downward in the non-surgical and surgical groups, respectively, during the retention period. Perhaps surprisingly, a small amount of incisal extrusion (0.4mm) somewhat compensated for the molar extrusion in the TADs group.

It is worth noting that the mean treatment duration was considerably (12 months) longer in the non-surgical group, with treatment taking over 34 months in the non-surgical and 22 months in the surgical groups, respectively.

What did I think?

I liked this study. There are issues with the methodology as this was essentially a convenience sample with an associated risk of selection bias. In particular, matching surgical and non-surgical cases is difficult. Indeed, we may be ‘comparing apples and oranges. Nevertheless, the participants did appear to be reasonably well-matched.

It is also likely that successful patients only were selected. Therefore, we cannot be sure how predictable both treatment approaches were in correcting the original malocclusion.

The results were interesting. I have always assumed that molar intrusion is relatively stable, with the forces from the posterior occlusion likely to reinforce the treatment-induced changes over time. However, this theory was not borne out in this study, with some molar extrusion observed in both groups. Furthermore, the incisors extruded by a small amount in the TADs group, compensating for the relapse in the molar region.

There are a range of different mechanisms for producing maxillary molar intrusion. The authors used a large number of screws but no palatal auxiliaries. With the advent of 3D printing, we may only be constrained by our imagination and ingenuity. There is, therefore, a myriad of ways of delivering more predictable intrusive forces to the posterior dentition. Therefore, this treatment approach will likely be used more and more over time. Nevertheless, it is reassuring to have some evidence that this approach may be as stable as surgical approaches.

What can we conclude?

Based on the present study’s limitations, there seems to be little to choose between TADs and orthognathic surgery regarding the stability of AOB closure. On this basis, I wonder whether a prospective study with random allocation of participants to surgical or non-surgical open bite correction could now be justified. While this may be the case, I would opt to have the TAD-based treatment every time. To paraphrase Peter Greco, ‘less invasive and equally meeting our objectives’.

Professor of Orthodontics, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Ireland

A 3.3 – 3.6mm AOB doesn’t sound like much to require orthognathic surgery? If the simpler treatment provides a similar result I would go for it every time. I’m sure my patients would agree!

It would have been nice to also include MEAW or GEAW as well to this in order to address all common methods of AOB treatment. Some might suggest CAT as well. OF course, that would be a huge study. One aspect which I feel is often overlooked is what is happening to the condyle, especially if intruding molars is leading to “loading” the condyle and increased pressure on it. This never seems to be mentioned at all.

Hi Mark,

The condyles etc are likely to be subjected to a ‘shock’ by the sudden effects of maxillary impaction whereas a gradual reduction in the alveolar process height, and consequential reduction in the face height, would allow the TMJ etc time to adapt. A Turkish paper, published in the EJO specifically assessed the effects of molar intrusion, albeit with more invasive zygomatic plates, and found no TMJ / muscle problems – Akan S, Kocadereli I, Aktas A, Taşar F. Effects of maxillary molar intrusion with zygomatic anchorage on the stomatognathic system in anterior open bite patients. Eur J Orthod 2013; 35: 93-102.

From an anecdotal perspective, I’ve never encountered any TMJ issues in over 60 molar intrusion cases, nor seen any evidence of condylar resorption (unlike the potential for idiopathic condylar resorption in surgical cases).

I fully agree with your perspective on this Padhraig, although it may be difficult to recruit patients to a RCT since their consent process would need to include discussion of the unfavourable nasal changes and morbidity associated with maxillary surgery. There’s also the risk of inadvertent maxillary advancement rather than a pure impaction movement. In the absence of this level of evidence, if there’s any doubt then I find it best to book a joint orthognathic consultation so that both options can be clearly explored and discussed. I can think of one young female whose mouth was too small for posterior alveolar (mini-implant instrument) access and needed surgery instead, but otherwise can’t recall any ‘simple’ AOB patient electing to have surgery in the last 10 or so years. My surgical colleagues are also happy with this change of clinical practice since they’ve plenty of other work to occupy them and view molar intrusion as the best option for patients too.

NEW PERSPECTIVE:

You could allow the NATURAL PROCESS OF CHEWNG AND WEAR to naturally intrude, wear, and compress the molar area, allowing the mandible to close more, narrowing the anterior gap. As long as they can chew , then there is no need to do any intervention. In fact, the tongue may have made the extra space that is needed for the airway and spinal posture- and in this regard, dentists should view AOB as OPTIMAL- one of the many mechanisms by which nature can create more tongue space. To “correct” ABO could be to inflict harm without any benefit.