Is orthodontic research poor? The Pyramid of Denial revisited

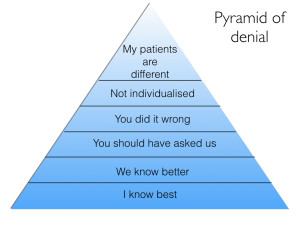

This blog post is about the rejection of research findings. I have decided to revisit the ‘Pyramid of Denial” which outlines the reason for illogical rejection of research.

One of my earliest blog posts was about a lecture that I gave at a symposium on early treatment. As part of my presentation I discussed the reasons that people put forward when they rejected or ignored research. I based this on feedback from questions that people asked at lectures, social media discussions and corridor conversations with the “great and good” of orthodontics.

Firstly, I would like to point out that I am not encouraging the blind acceptance of all research findings. We also need to remember that evidence based care is not solely based on the results of clinical trials.

However, I would like to discuss the rejection of findings in the absence of a proper critical appraisal. This led me to propose the Pyramid of Denial.

Lets have a look at the levels of denial

I know best

This means that a person feels that despite the evidence from the research project, they simply do not agree with the findings. In effect, they have decided to prioritise their clinical experience over the research findings.

We know best

This is when a group of people ignore the evidence and put forward a rebuttal. Again, this is often based on clinical experience or financial other influences?

You should have asked us?

I first became aware of this reason when we published the results of our studies into Class II treatment. Several “orthodontic authorities” told me that the results of the trials were disappointing and it was a real shame that we had not discussed the treatment with them. They felt that we had made mistakes in the design of our appliances and choice of mechanics. For example, someone told me that the Twin Blocks we used did not work because of the design of the lower molar clasps.

In some ways they were pointing out that the studies were subject to proficiency bias. However, when we set up the studies we agreed as a group on treatment protocols. We also held courses on the use of our appliances.

These comments are often about made about trials, and while they may be valuable, we should interpret these with caution.

You did it wrong?

They suggest that the study was simply flawed. We know that the publication of a study does not always guarantee that it is good. As a result, we need to use our scientific knowledge and interpret the findings with respect to methodological errors. I hope that this blog and other methods of critical appraisal can help with this.

Unfortunately, people propose spurious reasons for the rejection of research findings. For example, they feel that their preferred outcomes were not measured. They may also suggest that there are no outcomes relevant to the treatment that they provide. Interestingly, this is becoming more common with the discovery of orthodontics to cure breathing problems. Most orthodontic trials do not include measures of breathing and perhaps investigators should include these, if only to answer the “orthodontic breathing physicians” points.

Not individualised

A common criticism of trials is that the participants are treated “like a number”. Consequently, treatment is so tightly prescribed that care cannot be individualised. In effect, the investigators are not evaluating the “art of orthodontics”. I strongly feel that this is incorrect. We need to remember that the operators in a trial are ethically bound to treat the patient to the best of their ability. This means that they adapt their mechanics to provide optimum care. This also ensures that the study has external validity. Furthermore, it would not be ethical to treat a patient exactly to the study protocol if they recognised that they were doing harm.

My patients are different

The person rejects the findings because they are not applicable to their patients. This means that their patients are so different that they are genetically, sociologically and morphologically different from those in the trial. There is little to be said here..

Pyramid of denial bingo

Sometimes when I look at these comments on a study. I play a form of bingo and count the number of time that the levels of denial are stated. I cannot help feeling that there is a positive association between the “denial” score and the level of quackery.

Lets have a chat about this..

I learn a lot from your articles. Orthodontics student from Brazil here. My teacher Prof. Guilherme Thiesen told me about your blog. Thanks for sharing your knowledge.

This phenomenon is not limited to orthodontic research. In the US we are having a significant rejection of need for routine vaccination that is causing outbreaks of measles and flu and there seems to be no way to convince people of the safety and need for protection of the public at large.

Interesting points. I think one of the problems we face is that we sometimes consider that an individual trial provides a definitive answer. It actually answers a very specific question with some degree of uncertainty. It is up to us then to “blend” the findings form the specific study with others published before and then consider all this information as the scientific evidence part of the evidence-based triad (others being what the patient wants/expects and the clinician’s experience).

Also in some clinical situations although the evidence suggests that treatment A is more efficient than treatment B through an informed consent process the patient may actually go with treatment B regardless of the evidence based on other facts (cost, treatment time, comfort, etc.). Somehow our discussion goes into taking extreme positions and life shows us that is all about scales of grey.

I think is time to have a good discussion about informed consent process in day-to-day practice. Are we doing the best we can in this regard?

I think many of these studies should be done with “real” patients, not “ideal” patients. The biomechanical design that is shown in the works does not have occlusal, muscular, and bone quality differences that we have in our patient.

Kevin: I am sure there is a very “human” reason that psychologists can attribute to denial in the face of mounting evidence. Clearly it is more than in the field of orthodontics or even science. Political evidence of such is obvious to us all today. Why do people deny climate change? Whatever the reason, it is not good. In fact people who deny, believe very strongly that they (and they have large numbers and are herd like) are correct. It is a belief. It is passionate. They are not not open to discourse or looking at any evidence that may be presented with an open mind because their mind is made up. I say they but really the “they” are often many like us. Smart and successful people. So the question is why do they think the way they they and how do they formulate their intellectual constructs and belief system? Is it just part of human nature? How do we overcome this bias for the good of us all?

Shiva, You are exactly right about how people feel about their incorrect beliefs. The book “Thinking Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman (PhD psychologist, Nobel prize winner) was a best seller and is a very readable explanation of all of the facets of how and why people hold and cling to beliefs that are not true. (spoiler alert: The brain defaults to Gut feeling/intuition mode which always overpowers rational/scientific thinking mode unless a person consciously makes an effort to seek out the rational/scientific answer.) It was written specifically to answer the question you posed.

These are all variations on various logical fallacies or arguments, one of the most common being the argument from authority (ie I’m an expert so I know best). Thinking your patients are exceptional is called special pleading. I’m always a bit puzzled by the art vs science argument, ie orthodontics is an art so you can do whatever you want. this is plainly untrue. Because of the cosmetic nature of treatment then there will be variation in opinion re what should be treated and what the end result should be; but the manipulation and use of braces should be testable so as to optimise their use. This variation will either be in the brace itself, the patient or the skill (or craft or experience, not really art) of the operator. It appears currently that the brace used makes little difference. Patient variation we probably can’t do anything about as yet. Erm, I’m not aware of any studies comparing good to bad operators (would be a bit difficult to do I guess)

thanks for that

Do you have a hierarchy of research that is most problematic to ignore?

The “my patients are different” argument might have some weight if there are a wide range of things that can be different in patients that aren’t standardised in a study. I think a lot of studies go to publication with groups of 30 subjects and 30 controls- which is a magic number for acceptable confidence and power. But 30 patients walking in to my practice are likely to have a fair variety of differences even if they share an overjet or an age or a gender. Or all three.

Can you talk about the numbers you need to even out common variables?

Stephen Murray

swordsortho.com

Thank you for the blog and the comments.. I agree Stephen, that Orthodontic research is really important and that we should always look for the evidence for our treatment decisions and be aware of our own bias… but neither does the evidence provide us with precise formulas or exact ‘recipes’ for treatment planning for every case.

I think of it as using the imperfect, incomplete and improving evidence base we do have to continually improve our critical thinking and translate that into our clinical practice when discussing the options with each patient. That openness to learning and progressing also keeps us engaged!

To make a light hearted analogy with food… the top chefs don’t usually follow someone else’s recipe either.. but they understand the key principles and rules of the art of cooking from their training and mentored experience .. understanding their ingredients, flavours, techniques, timings and presentation, they can continually review, reflect and also understand their customers to create something we appreciate as wonderful.

A cook with poor understanding and technique will not create something as good with the same ingredients and limited thinking will prevent them from improving!

I strive to be a better cook and clinician!

Dear Kevin as I asked you before, is it possible to be critical (sometimes) with the use of Evidence Based and the external validity of some of its conclusions without being thrown out of the church of science in the hell of the Pyramid of denial ?

I really value your dedication, I always read your blog, I value your research and I share the same concerns about our Profession.

But let me give you a familiar example.

In your beautiful RCTs ( you well deserved all the awards for it) on Twin block the Inclusive Criteria were Class 2 patients with 7 mm of Overjet or more …..

Can we reduce a class 2 to one single problem? The need of the scientific methodology (we can investigate one problem at the time), is the same of the clinical reality?

The way You posed the question implies already most of the answer: since a Class 2 is considered an augmented Overjet, the criteria of success should be the Overjet correction.

Therefore we need an empirically validated overjet corrector (twin block, Herbst, HG ….) whose efficacy should be investigated in a randomized trial …. (always without extractions in your model)….

In a randomized trial the assignment of the treatment package (ie Twin Block) is not chosen by the doctor but by a 3rd person on the phone. Therefore simply apply the prescription; if the doctor thinks that for good reasons (Esthetics, growth, need for extractions…) the appliance should be discontinued he will cause a drop out…. with all the consequences on the validity of the study.

Every exercise of clinical judgement represents a threat to the heart of RCTs. RCTs need a treatment design which minimize the possibility of surprises.

Also we should consider that RCTs can evaluate only existing treatments, they cannot develop new and better ones.

Research can be very useful as long as we make sure that the clinical reality to which is applied has not been misrepresented to satisfy the demands of the research.

I sense the risk that Evidence based instead of being a powerful tool to confirm what we know, contributes to create a constant divide between real therapies and experimental models.

It is important to find well proven answers but it is far better an approximate answer to the right question than an exact answer to the wrong question.

This does not mean that we do not need Scientific evidence or that we are in the Kingdom of salesmen.

Grazie Renato

Hi Renato, thanks for the comments and this is a good discussion. The question about the inclusion of subjects in an RCT is interesting. I think that it is important that this reflects the reality of clinical practice in its various settings. For example, when we did the twin block studies in the UK, the main treatment for children with increased overjets was the twin block, followed by non ext/ext treatment etc. This is what we tested in the study. The other important concept was that we had very large sample sizes. This enabled us to have a broad inclusion criteria and then carry out sub group analysis to evaluate the effect of skeletal discrepancy and maturation stage etc. In fact we found that these variables did not have an effect. One of the problems with small studies is that they do not do this and I agree that simply putting a study of Class II cases with >7mm overjets with a sample size of 30, will make the study susceptible to the effects of individual variation and this is the point that you have made.

I think that RCTS can be used to develop new treatments. For example, if someone had decided to do a RCT of some of the methods to speed up tooth movement before they were widely promoted, we would have the answer that they do not work.

However, I agree with your general points and the way forwards is to plan studies that have large numbers and ask clinically relevant questions. Ortho trials have come a long way in the last 15 years and people now need to take a forward step and continue to make improvements. I think that this would be a good subject for a blog post! Thanks for the great comments.

Dear Dr. O’Brien,

thank you for the pyramid of denial as an aplicable model of explanation how many colleagues deal with scientific evidence. Right now I’m writing a review about the Damon bracket in German language for a second-class German-language journal. My review is in accordance with Wright et al., Journal of Orthodontics 2011, but integrates the Damon studies published since then.

I kindly ask for permission to reproduce your illustrations of the two pyramids of evidence and denial in my article under correct reference to your blog.

Sincerely, Henning Madsen

Regarding the subject of evidence-based dentistry, it is undeniable that there are contradictions, limitations, errors in the methods, biases, etc.

With this I do not mean that I am against them, or that I am only interested in those that are in favor of my thinking, I think they are very good, it is a great advance but like every tool has limitations, it has virtues and errors.

It is always said that when making decisions we must consider the triad based on evidence: available clinical evidence, individual clinical experience and taking into account the values and preferences of the patient, none of these is more important than the others.

However, when talking about the pyramid in evidence, meta-analyzes are ranked at the top and clinical experience is relegated or despised, this is incongruous with the triad.

In this sense, a clinical case presided over with a rigorous scientific method is as valid as a systematized investigation, we have to understand that the scientific method is predominantly experiential, since observation and experimentation are used, what better way to do science than in the same field of action?

The great recrimination against evidence-based medicine / Dentistry is that it is made behind a monitor not in the same place where the events are presented, it is not field research, the meta-analyzes are a selection of cases that ultimately depend From the criterion of the researcher, his thinking, his training and scale of values, this initially implies a great bias.

In this order of ideas, the data extracted may lack a context, a frame of reference, and it may only be a dance of numbers without real value, so everyone can do research, draw or make their own evidence, and it can be totally opposite to each other, this is not unusual.

In addition, everyone can do many things, however they are not always correct and desirable, we have a biological framework to respect, we can move, pull, push, modify a tooth, a bone, a tissue towards the front, upwards, to the left, so many mm. etc., but that it can be done does not mean that it is good for the patient, for their biology, for their health and homeostasis.

We can find a lot about this in meta-analyzes or in systematized research, a lot of data is obtained but without understanding whether it is good for the patient or not.

As I said, OBE is a great advance, it has helped a lot in clinical practice, but it is a fallible tool that must be used judiciously and above all with solid foundations, respecting biological principles.