Standing on the shoulders of a giant: WR Proffit lecture

I was very honoured to give the first WR Proffit lecture at the AAO congress a few weeks ago. I learnt a lot by preparing it and I thought that I should write it up and publish it on my blog. I hope that you find it interesting.

It has been an exciting couple of weeks on my blog with two posts that are not about mainstream orthodontics. This post is about orthodontics.

When I did my background work on the Proffit lecture, I looked back at Bill Proffit’s immense contribution to orthodontics in terms of his research, teaching and accessibility. This brought a lot of the issues that are relevant to contemporary orthodontics into sharp focus. As a result, I have decided to write up my lecture to share my feelings about his work more widely than just the AAO lecture theatre.

I am going to take up the next three posts with this subject. I hope that this makes you reflect as much as I did. I am going to include the main slides to illustrate some of the points that I made. I hope that this does not slow down the servers.

Evidence-based orthodontics

When the evidence-based care movements started in dentistry and orthodontics, they placed great emphasis on the importance of evidence derived from clinical trials. Over the years they have changed their viewpoint to recognise that in the “real world” evidence-based care is based around clinical experience, research findings and patients opinion. Importantly, if research evidence is available we should place greater emphasis on it than clinical opinion. However, if there is very limited or no research evidence then we can only base our treatment decisions on clinical opinion. This concept and thread ran throughout Proffit’s work and he gently emphasised the importance of both these strands in his research and teaching. I would now like to look at three papers, which illustrated the sheer breadth of his research and the importance of his findings.

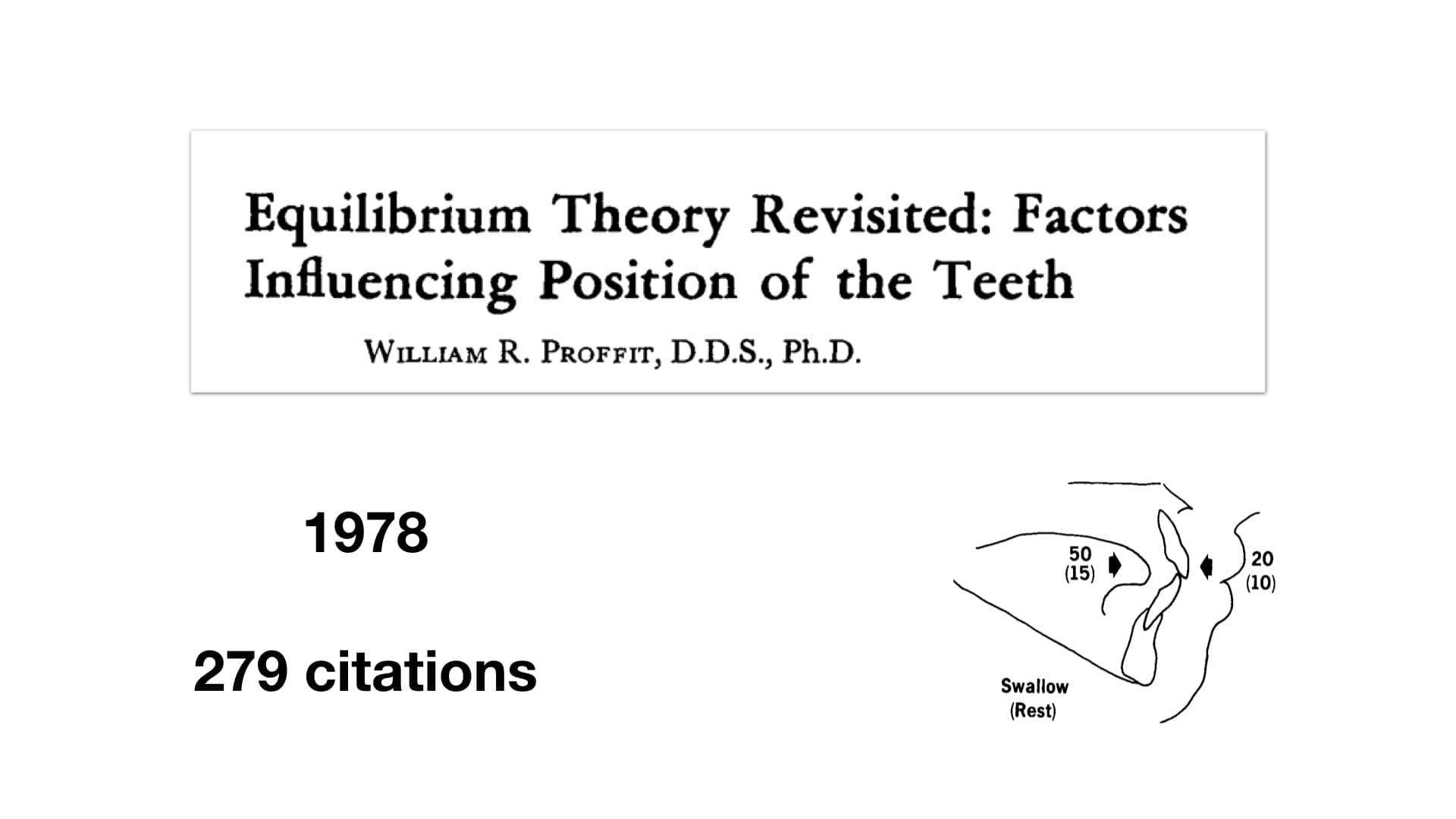

Equilibrium Theory Revisited

When I heard that he had died, I dedicated a blog post to him and reviewed this paper. I am not going to repeat this post, but I will reconsider some of the points that I made.

Firstly, this was a classic orthodontic paper and I recommend that you read it, even if you have read it previously. His main thesis was that there is equilibrium, in the mouth and craniofacial region, that governs the position of the teeth.

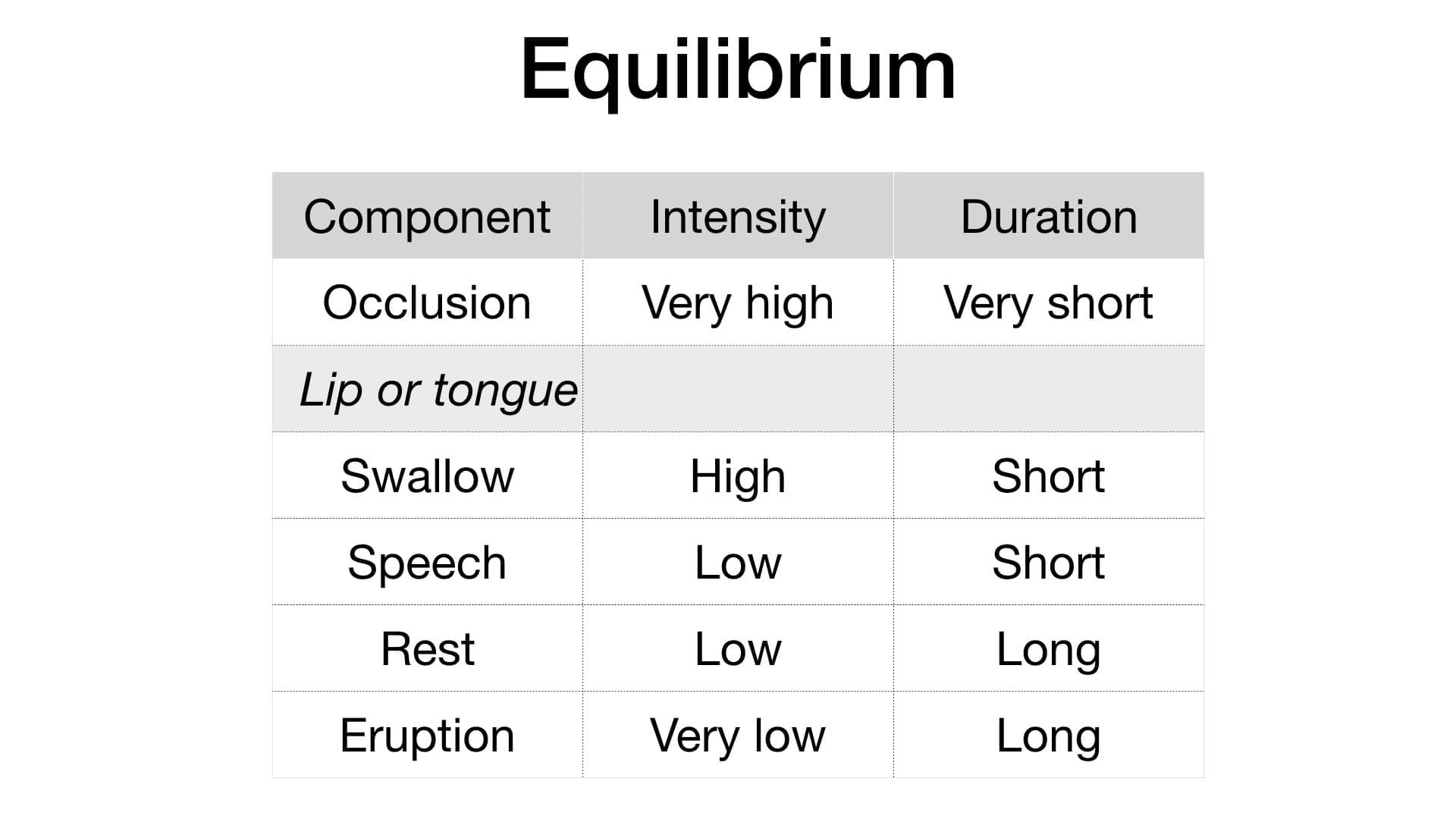

His most important concept was that the position of the teeth is influenced by pressures that are of low force and long duration. When we look at the origin of these forces, the most significant influence on the equilibrium is likely to be the rest position of the lips and tongue. All of the others, for example, swallowing are unlikely to have an influence.

He went on to explain that the equilibrium is influenced by a combination of genetics and environment. As a result, we have to consider the importance of these two factors, as our beliefs may influence our treatment decisions. For example, if we believe that genetics is more important than the environment, then we are more likely to extract teeth as part of our treatment plans. However, if we feel that the environment is of greater importance, and can be modified, then we are more likely to decide on growth modification, expansionism and non-extraction treatment. We should think about what we are doing.

While these concepts are simple, his overall conclusion was rather vague

“It is difficult to place the components of the equilibrium in perspective of aetiology”.

I have taken this to mean that there are several interpretations of the paper. This is the strength of the article that sets it apart from so much contemporary work. In effect, you have to read the paper and come to your own conclusions.

My own conclusions are that equilibrium is significant and there is no research evidence that suggests that it can be completely overcome. Therefore, we should carefully try to evaluate the effect of the equilibrium for all our patients and then take the relevant treatment decision. This means that we should not adopt a “cookbook” approach to treatment and treat all our patients with one method, albeit non-extraction, extraction, expansion or magical methods of growth modification.

Early Class II treatment.

This was the paper that he wrote with Kitty Tulloch and Ceib Philips. Kitty was the first author. Most of us are familiar with this paper. It had a profound effect on the subject of early treatment, but perhaps more importantly, on the way that investigators carried out orthodontic research.

The great thing about this study was that it was very ambitious. Nevertheless, they asked this simple question.

“Is early treatment for Class II malocclusion effective”?

They defined effectiveness, as the change in a limited number of cephalometric variables, number of attendances and duration of treatment.

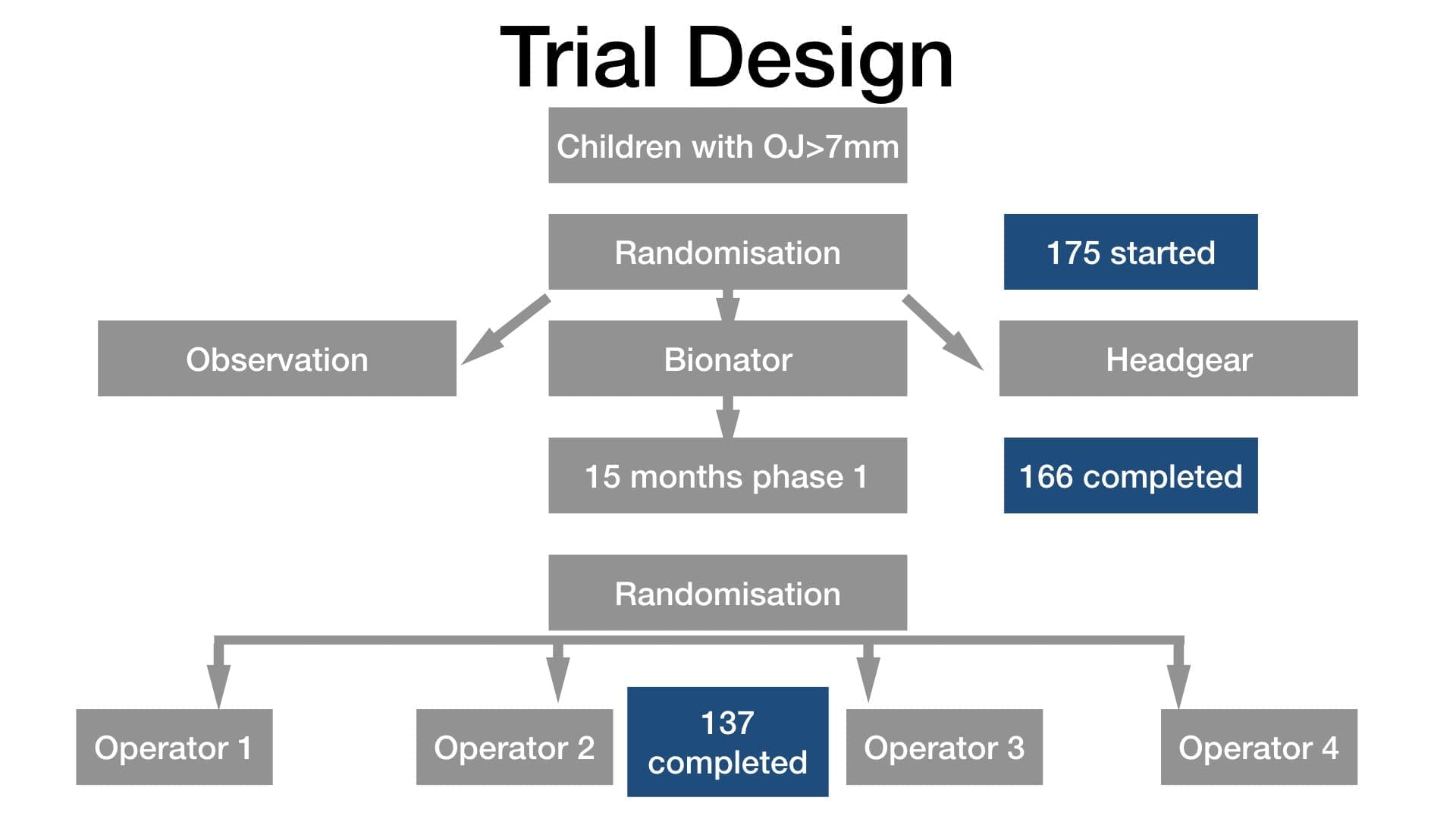

The design was simple.

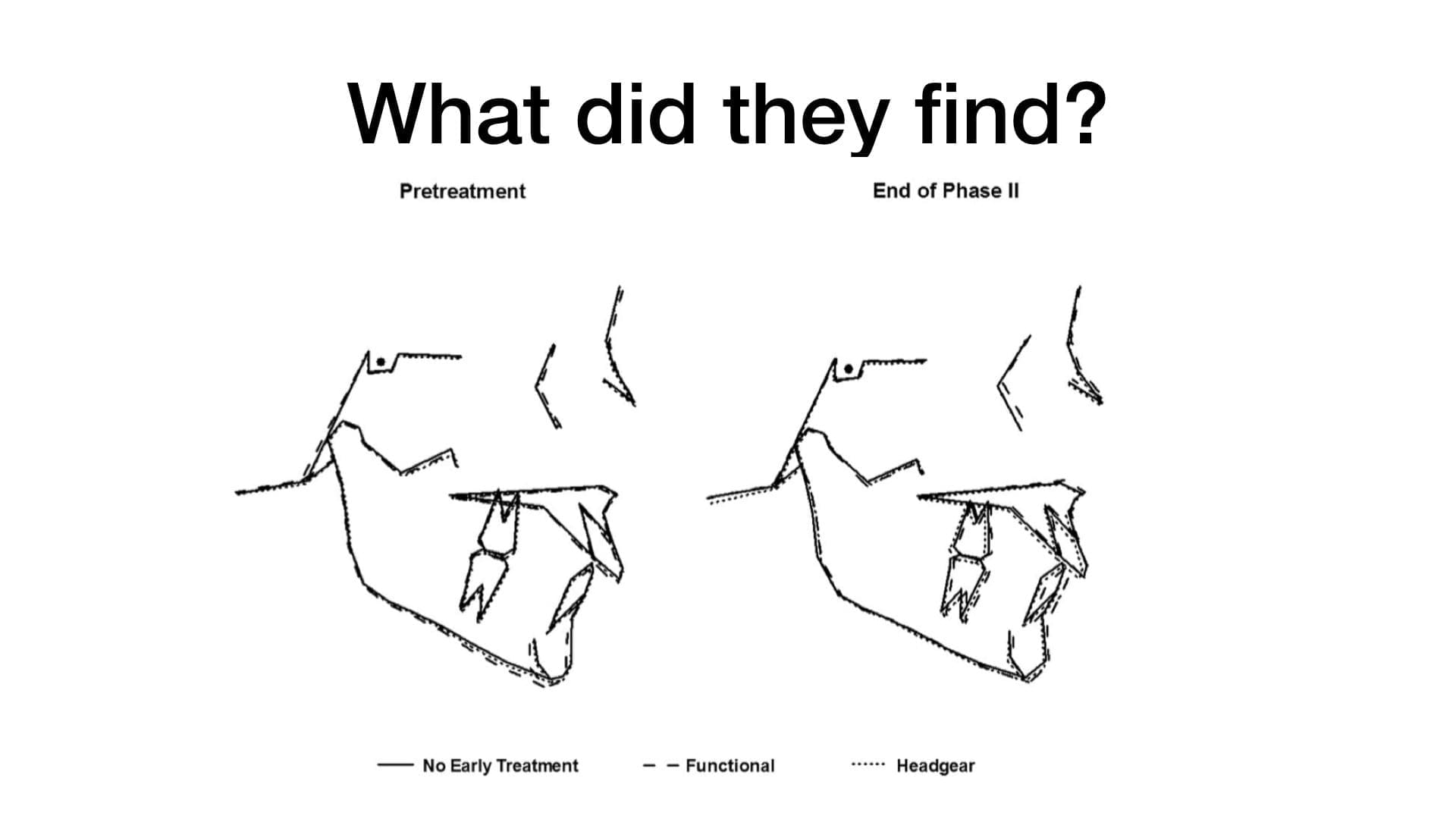

They presented their data in a straightforward and precise way by using these superimpositions. In effect, they showed that there were no differences between the interventions at the end of all orthodontic treatment. These pictures were so clear that you did not need statistics to understand that there was a minimum effect size.

Their brilliant conclusion was;

“Early treatment should not be thought of as an efficient way of treating most Class II children”.

This is very subtle because they do not state that early treatment is not effective. They simply point out that it is not the preferred treatment for most class II children. Importantly, this makes the reader look more closely at the data and then feed this into their own treatment decisions. Again, it makes you think about what you do.

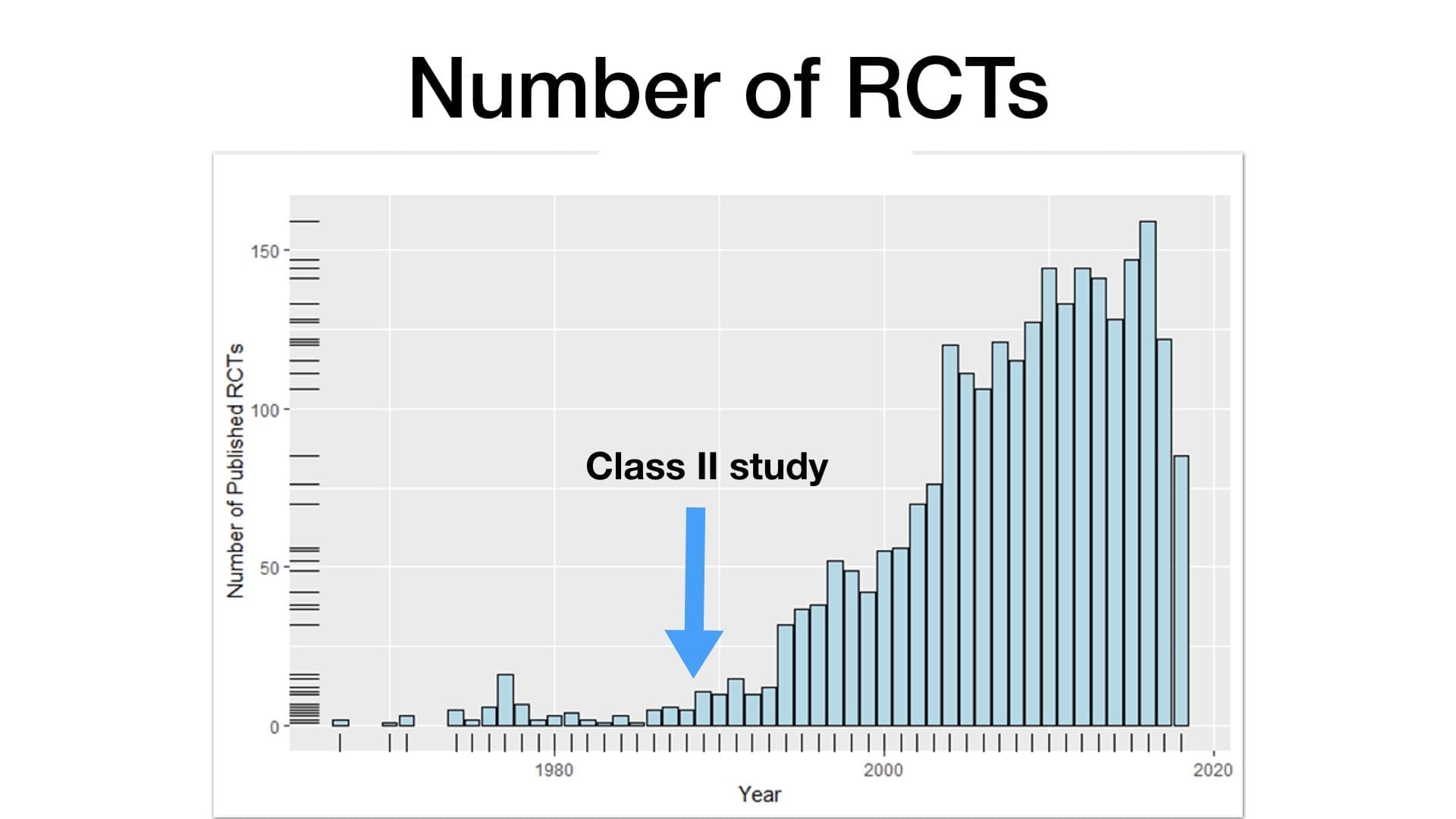

The other important consequence of this study was that Kitty Tulloch and Bill Proffit included descriptions of their trial in their lectures and publications. This had an effect of publicising the role of trials in clinical research, and potentially led to more trials being done. This is nicely shown in this graphic, which illustrates a rapid increase in orthodontic clinical trials in the early 1990s. I think that it is no coincidence that this explosion in trials occurred at this time. In my opinion, this was a remarkable legacy. It indeed, persuaded me that clinical trials were the way forward for my own research work.

Stability of Orthognathic Surgery

I think that my choice of the third paper was a little unusual. I was not too familiar with this study. However, it caught my eye because it may have been the first use of “Big data” in orthodontic research. Phil Benson did an excellent post on this in 2017.

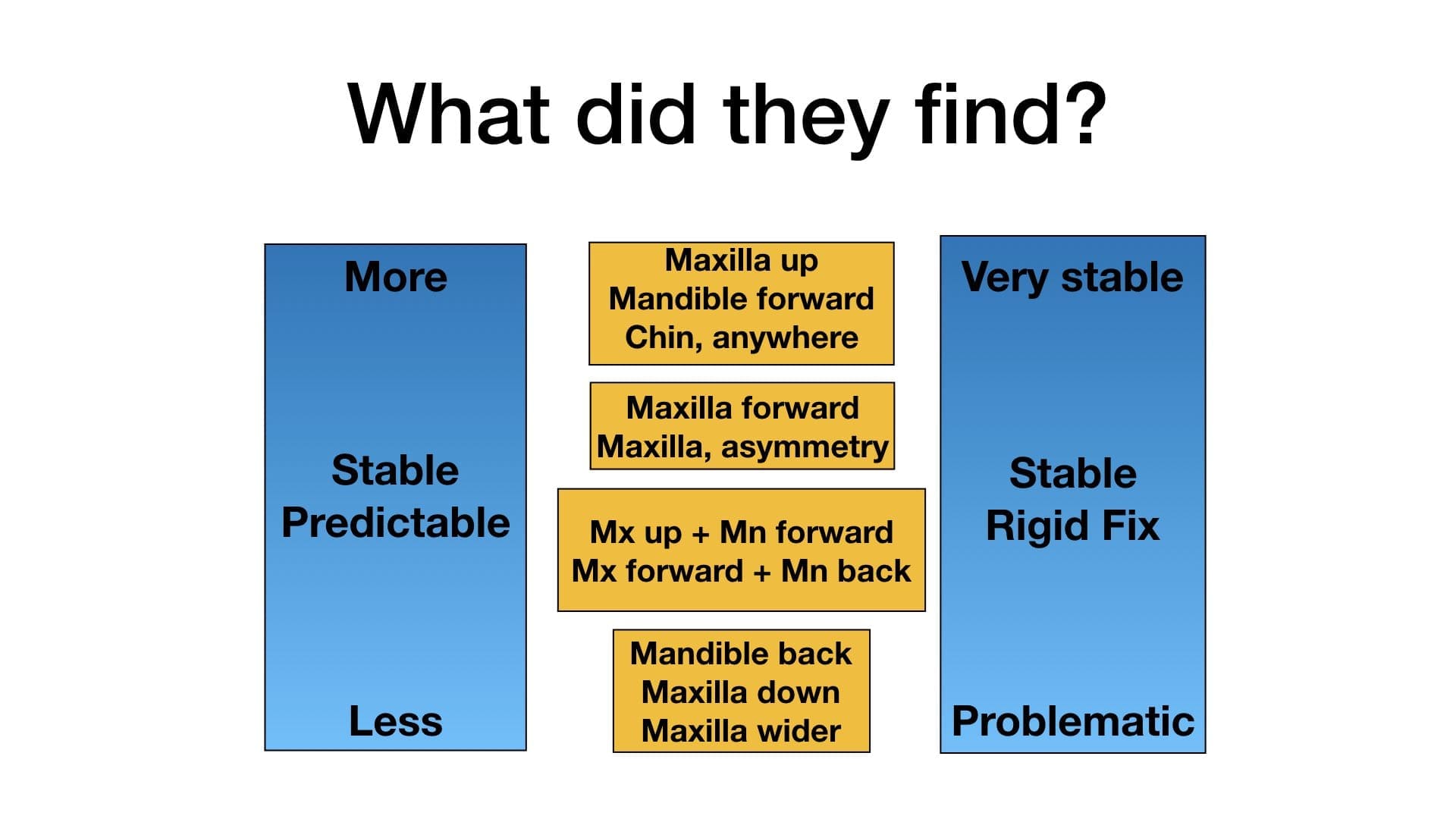

The study design was again simple. They interrogated data from the large cephalometric database that they had collected at UNC. They took the records of 2224 orthognathic surgery patients and analysed them to identify predictors of relapse. Currently, this approach is being put forwards as a method of reducing the cost of clinical research.

The other major step that he took was to define a clinically relevant change in cephalometric data as 2-4mm. This spared us the cephalometric festival of multiple comparisons in the search for statistical significance and getting excited about 0.75mm changes. These, of course, are meaningless. They also presented the information very simply in this graphic.

Again, he did not go into much detail on his overall conclusions. He expected the reader to interpret the data. My interpretation is that the soft tissues influence the stability of the surgical changes. Interestingly, this brings us back to the concept of equilibrium theory.

Next week I will post up the second part of my lecture, which is his book.

Emeritus Professor of Orthodontics, University of Manchester, UK.

Very well complied blog

Thank you for sharing the overview of those 3 articles Dr O’ Brein and your interpretation is priceless.kind regards

Dear Dr. O’Brien,

Your statement, “Again, he did not go into much detail on his overall conclusions. He expected the reader to interpret the data.”

I smiled as I read this for your words transported me back to the wonderful years of my Orthodontic Residency @ UNC Chapel Hill.

Seminars with Dr. Proffit were in equal measures challenging and deeply enjoyable. Quite simply, he taught us how to think!

A skill sorely needed especially after years of largely rote memorization – which Dental School tends to inculcate.

Dr. Proffit worked hard to turn us, his residents, into discerning diagnosticians.

Whenever he had a feeling that we did not grasp the full picture of what he was trying to convey; he never handed us the answers. Instead, he would say, “now let’s plow that trough a bit deeper.” a statement which often led to a lively discussion of the original source material and the findings we drew from it.

Dr. Proffit, as well as all of our excellent faculty members at Carolina, sought to create orthodontists armed with enough knowledge that we would be comfortable finding the proper course of treatment for all our future patients.

We were never simply handed easy answers, we had to work to find those answers. In the early months of residency we were provided with all the basic tools necessary for the adventure that would follow… Once we grasped those basic tools, it was our job to do the work and uncover those answers . In doing so, one learns so much more.

The knowledge that Dr. Proffit is gone still hurts deeply.

His passing was so very unexpected; only two days earlier he was at Carolina attending to his research and writing.

To learn from and to know such a truly exceptional person will always be one of the greatest gifts of my life.

However, Dr. Proffit was not simply a brilliant maverick of Orthodontics; he was also a deeply thoughtful and compassionate human being.

I would like all those who never had the opportunity to know him personally to fully appreciate that it is these qualities which informed Dr. Proffit’s daily actions and endeavors just as much as his insatiable curiosity and his admirable quest to advance Orthodontics and to set our specialty on a foundation solidly rooted in well done science.

Thank you most sincerely,

Dr. Madeline J Serrano

Thank you for sharing the overview of those 3 articles Dr O’ Brein and your interpretation is priceless.

Kevin very well compiled .

EPTheory is one of the most accepted theory.

“if we believe that genetics is more important than the environment, then we are more likely to extract teeth as part of our treatment plans. However, if we feel that the environment is of greater importance, and can be modified, then we are more likely to decide on growth modification, expansionism and non-extraction treatment.”

The truth lies somewhere in between. Great post, looking forward to the next post.

You are the sanity in the insanity of corporations hiring spokespeople to profess expertise while lacking any evidence base findings!!! You truly are a hero and please do not be bothered by the bullying of these so called experts. we need more people like you in the field of Orthodontics.

Kevin, I had the unique opportunity of sitting in your tribute to Bill Proffit. It was a special moment with the solemnity that Bill deserved. Congratulations in putting all this information together and making it an unforgettable moment for the audience.

Thank you Kevin for reviewing and refreshing our memory lane.

Very well compiled and Great Tribute to Dr Proffit.